The scales have tipped. The glass is overflowing. I’m not sure when the drop that caused the overflow happened, but it feels different now, the fact of women’s writing, women’s words in the world. As a child, a teenager in school, I felt the general tokenization of women. I received by osmosis (from textbooks, from teachers), the sense that “women writers” needed to be included in curricula to fill a quota, but that they weren’t quite as good as the writers that didn’t require a modifier (male writers).

Then, when trying to write, learning to write, there was the sense, also transmitted by teachers, anthologies, peers, that I should try to write to fit in with the men, to impress the men in the room, in the canon, at the publishers. Gradually, this fueled a rebellion and I wanted to read only women, discover women’s writing that wasn’t anthologized or talked about in institutions, and write like a woman (whatever that means, if anything). But this felt like a kind of isolation, marginalization in my reading and writing life. [The usual disclaimer: I’m writing from a mostly English-language, mostly American perspective…]

But the chauvinism isn’t a given now. The rejection of it is palpable! Women writers are becoming just writers, no modifier required. Joan Didion is the aspiration, not Norman Mailer. Women, who comprise the majority of fiction readers, now number among the critics. So many more varied women’s voices are being published, on a large scale, by major publishers, from mass market to literary. That’s not to say there’s still not a way to go, of course. This is the beginning and it feels great.

What’s struck me recently is that not only are new voices being published, but women writers from the past are being resurrected and appreciated. In the U.S., Eve Babitz, Lucia Berlin, Clarice Lispector, Elizabeth Hardwick, Penelope Fitzgerald, Renata Adler have all had a recent renaissance as major literary figures of the 20th century. (Parul Sehgal of the New York Times wrote an interesting piece about this phenomenon and paying attention to what caused the vanishing in the first place.) Not only was Zora Neale Hurston’s book on a former slave published in 2018, 90 years after it was written, it got a surprising amount of ink when it did (History.com, NPR, The Huffington Post, The New Yorker, The Daily Mail!).

I’ve been thinking of all of the Modernist women I skipped over in my education, whose work I still haven’t read. I was reading T.S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound hungrily, but skipped over Mina Loy, H.D. I didn’t know about Djuna Barnes, Kay Boyle, who were there all along, drinking and smoking with the dudes, and writing, too.

As someone with an interest but no particular expertise on visual art, I’ve been peripherally aware of a similar tendency in that realm, as well. I was delighted by Peter Schjeldahl decrying the title “Woman Impressionist” of the big 2018 Berthe Morisot show at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (“a great artist who is not so much underrated in standard art history as not rated at all”). There was the recent astounding Hilma Af Klint show at the Guggenheim. She was painting abstract forms in the early 20th century on her own, as part of a spiritual search, long before Kandinsky, and didn’t want to be shown in her time for fear of being misunderstood. There was Yayoi Kusama’s triumphant, late-career world domination, beginning with the blockbuster show at the Hirshhorn in 2017. A big Frida Kahlo show now at the Brooklyn Museum. Joan Mitchell’s work setting auction records. (I’d never heard of her before last year, but of course had heard of de Kooning and Pollock.) I’ve seen lots of Artemisia Gentileschi’s images pop up all over the Internet. Hopefully the art history books are being rewritten. These people, their work, have been there the whole time.

I don’t have the same evidence, but a sense or hope that this transformation–the recognition of women who were there all along, making history and culture–is happening in other areas, too, ones that I track less, like comedy, film, food, and science.

This resurrection of women from the past makes me think of an ancient civilization that’s discovered beneath the living city. It was there all along. We are excavating, removing the layers of dirt that was dumped on women’s work. We’re carefully lifting it up, dusting it, examining it, valuing it, attempting to connect it to other fragments. We’re realizing, too, what’s been lost and can’t be recovered.

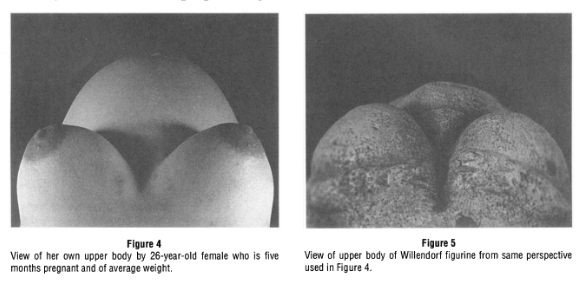

Evidence of this past civilization goes even further back. I don’t know why we’ve assumed it was only men drafting illuminated manuscripts, sculpting goddess figures, painting on cave walls, but we do, I do. We need scientific proof that it was possible women were doing these things, otherwise we don’t believe it, can’t picture it. I saw several articles making the rounds recently about flecks of blue lapis lazuli being found in the teeth of a 1,000 skull of a nun in a German monastery. It’s evidence that women, too, created beautiful illuminated manuscripts. There’s scientific proof that most cave paintings were done by women. And there’s the theory that “the first images

of the human figure [fertility goddesses] were made from the point of view of self rather than other” and “Paleolithic ‘Venus’ figurines represent ordinary women’s views of their own bodies.”

The uncovering of women’s part in our civilization and culture isn’t a physical discovering. It’s been there all along. We covered it up and made ourselves blind to it. We have to remove the layers of dirt from history books, museums, our own minds and consciousness…