My latest review is of an elegiac memoir of by an extraordinary woman about living in solitude in the wildest places, and watching them disappear. At the Chicago Review of Books.

Writer, editor, translator

My latest review is of an elegiac memoir of by an extraordinary woman about living in solitude in the wildest places, and watching them disappear. At the Chicago Review of Books.

For my book opinions and fledgling comics, subscribe to my always free newsletter, How to Play Hopscotch. You can also read archives there.

Sign up at megin.substack.com.

My round-up of “last year’s books” is coming a bit late as I’ve turned this annual tradition into quite the project, and I was busy writing book reviews. I decided to go ahead and finish it, as I mostly post this for my reader friends, and it doesn’t really matter when I get it up.

My round-up of “last year’s books” is coming a bit late as I’ve turned this annual tradition into quite the project, and I was busy writing book reviews. I decided to go ahead and finish it, as I mostly post this for my reader friends, and it doesn’t really matter when I get it up.

I love seeing other people’s book lists, friends and strangers alike, and I’m always so curious to see what someone is reading (on the bus, on their shelves). I started this annual round-up because I wanted to understand what I actually thought about a book, how much of it remained, and what my reading life as a whole amounted to. I decided to post it online (on a defunct anonymous book blog) so that I would complete the thought and actually finish the exercise. Then it became a way of sharing with my bookish friends scattered around the world, who I miss talking to. They’re not quite reviews, as I think a book review actual owes more to both the readers and writer (I hate summarizing plots, for example). Just a few thoughts.

As usual, the ranking is not necessarily based on literary excellence, but on how big an impact the book made on me (sparking new thoughts, feeling things, the lingering image); how likely I am to press it into a friend’s hand; how much of it remains months after reading it.

A note on book lists

Seeing all of the best of the year, best of the decade, best of the 21st century book lists at the end of 2019 wasn’t as fun as I’d anticipated. After these lists came the raft of lists most anticipated books of 2020. All of the lists started to feel like this endless, churning mass, or like a crowded conveyor belt of text that’s impossible to keep up with. Obviously this exclusive focus on what’s new is what keeps the publishing industry viable, but it must also be so disheartening for anyone who published a book 3 years ago, or 7 years ago, or 15 years, this feeling of only having a couple of months to make an impact.

I do love discovering a bold and new voice, who is speaking to our precise moment. But there should also be at least a little room in our shared cultural spaces (book coverage in newspapers, book sites like Electric Lit, etc.) to consider work beyond the months (weeks?) of its big debut… I saw some conversations around this on Twitter, with writers/critics attributing this myopic focus to the loss of dedicated book sections in newspapers, well paid book review gigs, etc. Books coverage being reduced to the “listification” of writing about brought by the internet.

It’s sad to lose some of the excitement around new book lists to this general sense of information overload I’ve been trying to keep my head above for the past few years. On the other hand, it’s less pressure to keep up, and maybe make my reading life more intentional.

On the subject of reading books other than what’s hot now, I’ve noticed that, since I began tracking my reading more closely, beginning in 2009, besides reading newish books I’m excited about, I’ve also kept up a steady parallel stream of books published by women in the 1970s. This wasn’t intentional. I think it’s partly because one writer leads me to another (e.g. Mary McCarthy led me to Elizabeth Hardwick), the fact that there’s been a revival of these writers in recent years who criminally went out of print (Renata Adler, Eve Babitz). I also think it’s because the 1970s were a time of intense, deep-thinking creative production, also in film and music. (The possible reasons why are whole other post.))

Overview

I read 33 fiction, nonfiction and poetry books. This number is higher than usual, I think in part because I broke up with The New Yorker in the spring (it’s an up-and-down relationship) and because I tried to get a grip on my social media addiction.

General trends in my reading life in 2019: Lots more nonfiction, mostly essay collections; lots more poetry read cover-to-cover rather than dipped in and out of; a decline in my reading of books in translation and books written in other languages, which I’m not happy about. I also felt a need to re-read books I’ve loved, so I’ve listed these last, as I’ve written about them at other times.

A few stats on the books I read:

1. A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk (Faber & Faber, 2001)

2019 was my year of Rachel Cusk, as it was I think for many people, as the conclusion to her pioneering “Faye” trilogy was published in 2018 and brought a lot of buzz. After tearing through a lot of her work, though, this memoir of becoming a mother strikes me as the most remarkable achievement. While I’m not a mother, I’ve thought a lot about parenthood over the years, and how it might change someone. (Or maybe not being a mother when most of the women in my life are is what’s made me all the more curious). How parenthood changes not only how you structure your life, how you structure your time, what you consider important, etc. which are things people usually talk about, but how it changes your sense of self – much harder to articulate—and what Cusk tackles in this memoir.

This isn’t a book exclusively for mothers, just as books about traveling around the world, or going to war, or being a chef aren’t only for readers who have done those things. I say this because it ticks me off the way the experience of motherhood is marginalized as something mainly of interest to mothers. Cusk tears down this ghettoization and the related sentimentality around motherhood and does a surgical (and hilarious) analysis of “the literature” on pregnancy and baby books. She considers the consciousness and existence of a baby on its own terms. She breaks down the complicated sense of being divided in two, a loss of a previous self, the almost-romantic obsessiveness between mother and baby… and a lot more. The world wasn’t ready for this book when it came out. Cusk was trashed as a whiner and even criticized as being a bad mother by her reviewers, and the book relegated to the “mommy war trenches,” rather than considered as a memoir of an intense human experience from a completely individual perspective, setting down thoughts and truths I don’t think have been articulated in print before.

Provenance: The American Book Center, Amsterdam

2. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil by Hannah Arendt (Penguin Books, this edition 1977, original pub date is 1963)

I’d heard a lot about Arendt’s work (and her name has become current again with the election of Trump), but was frankly intimidated as I don’t feel like my mind is capable of taking in anything labeled philosophy these days. I learned that this book was based on a series of controversial New Yorker articles published in the 60s from a 2012 German film called Hannah Arendt (recommended!), so I overcame my fear, thinking of this book as a very long New Yorker article.

I could write a whole essay about what I took away from this book. The short version in list form: as promised by the title, an analysis of the psychology and bureaucracy behind obedience to horrific crimes against humanity; an absolutely unwavering moral clarity, intent on seeing clearly through sentimentality and politics (she isn’t afraid to criticize the effect of these on the court proceedings for example, or to speak openly of the political motivations of Israel and Germany in the trial); the concise account of the “Final Solution” treated by country, a tremendous synthesis done in under 100 pages, revealing the sort of resistance that worked against the Nazis (in Scandinavia, for example), perceived as inexorable in other places; her style, which is acerbic, unflinching, erudite, confident.

It was Arendt’s tone that essentially what got her into trouble. Critics understandably were bothered by her being able to find anything funny about the situation, but I think this acerbic tone is a sign of her courage. Arendt demands truthfulness in language, and she refuses to hide behind platitudes. Cries of “Never Again” were already stale at the time she wrote this book (early 1960s), as the impunity so many of the perpetrators were granted in Germany and elsewhere was obvious. Sentiment and good intentions aren’t enough, only an international criminal court could serve as potential deterrent and retribution for these acts. (An institution that came to be! And for which I worked for 3 years!) It’s her faith in and respect in the power of language that allows her to see the humor in Eichmann’s use and abuse of language, his utter reliance on clichés and platitudes, especially about the worst acts committed by the Third Reich.

I used to define life difficulties as challenges to writing (or creative production, generally), but lately a different path has been apparent, writing as a way through them, although this is very, very hard, to plunge into the material. But maybe it’s a way out. This thought comes from contemplating the lives of amazing writers, who survived terrible things, but wrote through them. Writing as a way of surviving. I’m thinking of Natalia Ginzburg, who survived WWII through much hardship, including losing her beloved husband (who died imprisoned by the Fascists) and other family members; Marguerite Duras, who survived childhood with a mentally ill mother, lost a child, battled alcoholism, but wrote and made films through all of it. Arendt was a Jewish German woman who, though she fled the country before the worst was to come, but still bore witness to so much horror. To write something so clear, uncompromising (and even at times bemused), finding a way through the emotional, political, historical complications of the Holocaust (when it’s easier and understandable to retreat, to be too tired to pick up the pen) is an incredible act of strength and courage.

Origin: Boekenzolder (free book warehouse in Leiden!)

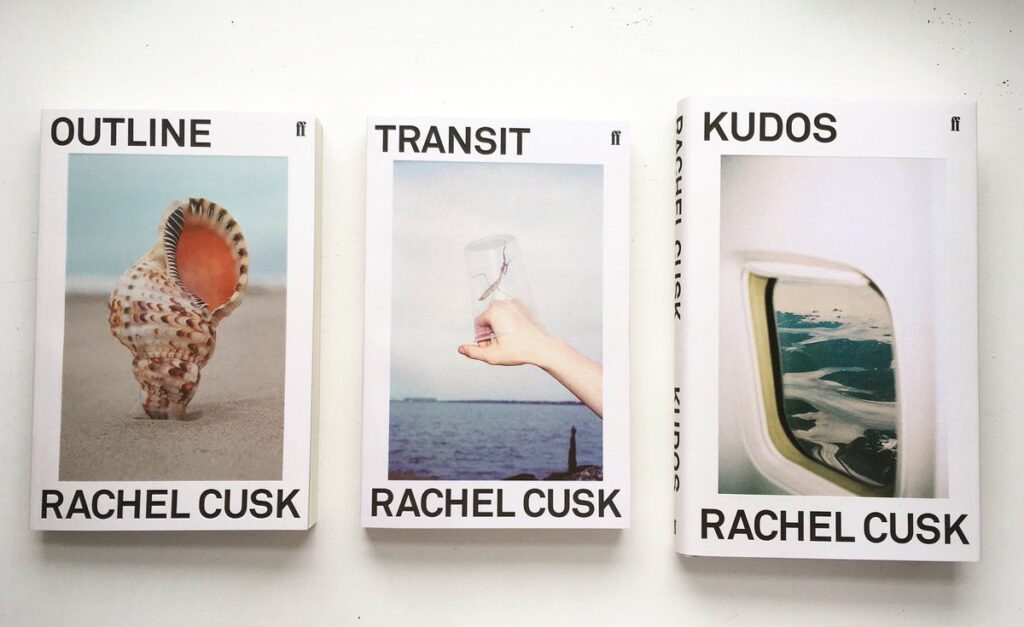

3. Outline by Rachel Cusk (Faber & Faber, 2014)

This is the first in Cusk’s so-called Faye trilogy. I loved:

– How this novel was formally experimental but still absolutely emotionally piercing. (Not much happens, it’s mostly made up of the narrator, a British writer teaching a workshop in Athens, retelling stories other people tell her.)

– How it gives you the dislocated feeling of travel, where your senses are heightened and the smallest details (a poster in a cafe) take on some yet-unknown significance.

– How Faye has a weary, post-traumatic tone, but still manages to throw shade (on the obnoxious and Irish writer, a fellow teacher, for example).

– How much it gets accomplished in 150 pages or so.

I wrote a lot more about this trilogy here.

Provenance: The American Book Center, The Hague

4. Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick (Virago Press, 1979)

A stunning polished gem of a novella. I got something akin to Stendhal syndrome from the first chapter of this book, which sounds dramatic, but is true. I felt physically overwhelmed by how good it was at the language level, and felt something like panic that I was incapable of taking it all in at once. I read the Paris Review interview with Hardwick after reading this, and she talks about how much of her process (and her favorite part of the writing process) is revision and polishing, which gave me a better sense of how writing of this intensity and caliber is possible.

A difficult read, not because of the plotlessness, which doesn’t tend to bother me, but the relentless grimness of the episodes within. A work about the autumn of life, memory, regret, getting old. I had more to say about it here.

Superficial side note: New York Review Books, the press I’m crushing hardest on lately, recently reissued this (along with much of Hardwick’s other work) with a much better cover in their beautiful editions.

Provenance: Boekenzolder (free book warehouse in Leiden!)

5. Ways of Seeing by John Berger (Penguin, 1972)

Have I mentioned I love concision? This is like a manifesto in that it’s slim and small, but you could start a revolution based on the ideas contained within, the questions it asks. For example: what was the social function of European painting? Why is the average person alienated from this direct line to our past? Why so many naked women? How do you look at a painting and how are you “supposed to” look at a painting? By art historian and novelist John Berger (oh just realized I have to put so many of his other books on my to-read, given the impact and brilliance of this one.)

This book is based on a BBC series produced in the 1970s, a little pocket paperback with black-and-white photos. A larger edition with full-color reproductions is desperately needed, given the content. Get on this, Penguin!

Provenance: Ordered from Better World Books

I am not so systematic about poetry, either reading or writing about it. But I don’t want to exclude poetry from my list, so below a few highlights from last year in no particular order.

Exciting discovery of the year:

Hinge & Sign: Poems, 1968-1993 by Heather McHugh (Wesleyan University Press, 1994)

My first encounter with McHugh. I immediately connected with this book of her selected work, which is such a rare and amazing thing with a book of poems. Here are a bunch at the Poetry Foundation site.

Origin: Bruised Apple Bookstore in Peekskill, NY, an old school huge used book and record store in a cozy spot.

On the mysteries of the feminine:

Isn’t Forever by Amy Key (Bloodaxe Books, 2018)

Playful and varied with form. Unapologetically feminine, melancholy, charming, lush poems by young British poet Amy Key. Read a few here.

Origin: Lent to me by my poet friend Lydia Unsworth (thank you, Lydia!), and then I purchased a copy of my own directly from Amy via Twitter!

For comforting long poems:

Like That by Matthew Yeager (Forklift Books, 2016)

I was missing my friend Matt, and reading his book again was a nice substitute for hanging out. These are funny, American, soulful, exuberant, ambitious. Poems by Matt here.

Origin: Gift from the poet.

Short & dark poems:

Dark Hour by Nadia de Vries (Dostoyevsky Wannabe, 2018)

Poems like a shot of espresso. Epigrammatic & ironic. Published by an enterprising UK-based press.

Origin: A swap with the lovely Amsterdam-based author.

Unexpected tropical, cheeky haikus:

On Some HispanoLuso Miniaturists by Mark Faunlagui (1913 Press, 2018)

Aware of sensual pleasures – food, sexual attraction, the new sensations of travel – but understated.

Origin: A gift from my generous publisher, 1913 Press.

Language equivalent of a spiritual retreat:

The Lyrics by Fanny Howe (Graywolf Press, 2011)

With some undivided attention, Fanny Howe’s poems will deliver you to a contemplative state. She is a pilgrim, wanderer, seer.

Origin: Purchased somewhere in NYC many years ago.

Chapbooks/Pamphlets

It took me this long to learn that the Brits call chapbooks “pamphlets,” which sounds a bit flimsy to my ears (I think of a pamphlet on preventing STDs), but who knows, maybe in a few years it will be rolling of my tongue like “queue” for line and “lift” for elevator do know, to my embarrassment…

These were all chapbooks that came in to my orbit last year, all by poet friends residing in the Netherlands:

Say cucumber by Lucia Dove (Broken Sleep Books)

I Have Not Led a Serious Life by Lydia Unsworth (above/ground press)

Grief Is the Only Thing That Flies by Laura Wetherington (Bateau Press)

This novel is by the author of The Dinner, probably the best known work of fiction by a Dutch writer in recent history (which I haven’t read). This book was written after that success. I picked it up at a bookstore clearance sale, thinking I should read more Dutch writers. First the positive: Koch is good at suspense. The story had me in its grip, and he can build a character, scene and clear narrative voice. This translation felt right, too. It isn’t ever conspicuous or awkward in its construction, but it also somehow transmitted a European voice (as opposed to an American or British one).

Unlikable protagonists have been a favored vehicle fiction in the past 20 years or so, including in television (Tony Soprano, Don Draper, Walter White) and movies (Young Adult), although, granted the male ones are more easily accepted by audiences than female ones (e.g. Moshfegh’s Eileen). Koch takes up this device, creating, it seems, the most unlikable person he could imagine: a misanthropic doctor who is disgusted by the human body; who treats mostly artists, but dislikes art; who views having daughters rather than sons as a misfortune; who sexually objectifies every woman who crosses his path, etc. I think the intention is a kind of black humor but I can’t help but suspect the author behind it took some delight in setting down views that have become unacceptable via his creation, which he can easily disown – “scientifically based” sexism, for example (men are wired to impregnate young women and women are wired to want to reproduce with successful men) and homophobia (anal sex is unnatural). I suspect the author more than his character, because much of that stuff, in the end, is gratuitous, not in service to the story. Even if we give the author the benefit of the doubt (as a reader should) and don’t entangle him with his character, the mechanics of the story itself raise some questions. For example, how rape is positioned as a plot motivator, or how a single anonymous gay character offers a sympathetic ear to the evil doctor after suffering humiliation at his hands.

Questions of author v. narrator aside, I also thought that for being a tightly plotted suspense story, the ending sort of collapses. While there is great tension from chapter to chapter, when you examine the ending, or start asking questions (e.g. why doesn’t a medical doctor consider the possibility of DNA evidence before assuming who has raped his daughter and deliberately spreading cancer in his body?), the whole thing sort of collapses. There are also at least two multi-paragraph descriptive passages involving semen, which are two too many in my view. In short: not recommended!

I was chatting with two women a a literary event this spring. They were both in their 50s, full of knowledge, and talking about their experiences with Stendhal syndrome, based on Stendhal’s experience when visiting Florence. It’s a (medically debated) condition of being physically overcome by a piece of art to the point of being dizzy, overwhelmed, weeping. (From Wikipedia: “The staff at Florence’s Santa Maria Nuova hospital are accustomed to tourists suffering from dizzy spells or disorientation after viewing the statue of David, the artworks of the Uffizi Gallery, and other historic relics of the Tuscan city.[1]“) One of the women said it had happened to her twice in her life, once seeing the opera made of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and the second time on seeing a Rothko painting, from across the room. The other woman had also experienced it with a painting. They turned expectantly to me, and I, embarrassed said that I hadn’t ever experienced it. But I thought it was better than lying about having experienced such a thing. I’d been dazzled by art, had a physical response to it, but never a kind of reaction they described.

Since then, I do think I experienced something like Stendhal syndrome reading the first 20 pages or so of Sleepless Nights. I didn’t break down weeping, but I felt dizzy, overcome, a little panicked as I moved from sentence to sentence. I couldn’t take the precision, the power of each one, the turns, the unexpected rightness of each image. I was anxious about not being able to take it all in, that I was unworthy or would need to read it a dozen times to take it in. It sounds so dramatic when I set it down like this, and I can’t say that it was pleasant, but the bottom line is that the writing is stunning.

However, I haven’t put this slim novel at the top of my list of recommended books because it is so melancholic and grim. It’s about faded glory, the bill collector arriving, the loneliness of old age, the winter of life. Not the best book to read as you’re staring down 40, turning the corner.

It took me a while to understand what Hardwick was doing with this book, what it was, but I also didn’t care that it wasn’t immediately apparent, because of the deliciousness of the language. The narrator is a woman, named Elizabeth. Over the course of the book, she recalls people in her life, tracing their fates over time. Often the people are downtrodden, ill-fated: Billie Holiday in a Harlem club; residents of a New York City rooming house; a Jewish Dutch doctor who survived the Nazi camps, had life-affirming affairs in Amsterdam afterwards, in his old age, with his bitter alcoholic wife; a lover from Elizabeth’s youth, abandoned by his long-time partner, come to see her to complain, his life has amounted to not-much; the cleaning women she has known, their difficult lives, difficult ends of lives. It would be sort of unbearable if the writing weren’t so alive in contrast.

Hardwick joins the list of criminally under-appreciated women who were writing in the 60s and 70s, and who I’ve had to discover on my own. They include Renata Adler, Eve Babitz, Grace Paley… (Obviously Susan Sontag, Joan Didion, and Hannah Arendt are/were more visible, but I like that they inhabited the same world and had contact with each other at the time, even if “only” through their words.)

Rachel Cusk has become my 2019 obsession, by which I mean that her books have been the irresistible ones, the ones I’m compelled to buy despite the piles of unread ones in the house. It’s because of the precision of her writing, her descriptions of individuals, landscapes, rooms, and the atmospheres in the rooms, that are concise and vivid and simultaneously unusual and spot-on. The way emotion is intensely present but not overstated on the page. Her sense of humor, grim and dry, and the way she takes on difficult subjects without looking away. The way she dives straight into the essential question, problem, point of fracture or heartbreak.

Her so-called “Outline” or “Faye” trilogy, feels so much of this time, though I haven’t entirely figured out why. I don’t just mean references to Brexit or sideways commentary on the state of the publishing industry, though those kinds of things do make an appearance. I mean the narrative experiment going on, in terms of both the position Cusk takes as an author and Faye takes as a narrator.

Author v. narrator v. narrative

Cusk has essentially said that she had to step away from writing as herself after being viciously, personally attacked by the press, and some readers, following the publication of her memoirs on becoming a mother (A Life’s Work, which is stunning and hilarious and brilliant) and her divorce (Aftermath, which I haven’t read).

The author has put aside the construct of a plot, perhaps distrusting whatever use an invented storyline can be to our lives, and instead seeks to dig into the stories people tell each other or tell about themselves. The form is experimental in that the narrator, Faye, is a writer who hides behind the retelling of other people’s stories. In the first book, she travels to Athens to teach a writing workshop; she buys and renovates an apartment in London in the second; and attends a writer’s conference in Portugal in the third. We learn that she is divorced, that she has two children. This is the slender framework of the trilogy. The meat of the books are the stories of the people she meets – strangers on airplanes, her writing students, her hairdresser, old friends, journalists who interview her. She retells and reshapes their accounts and confessions. Their stories are shards of a mirror that refract and reflect each other, and Faye in a more subtle way. There are many possible themes, or maybe these are better phrased as questions: What happens after you let go of the story of the life you imagined for yourself? What do parents do to children? What do men do to women? What does suffering bring? What does it create? What is static and what is changeable about the self? What generates the creative act?

It’s significant that Faye is a writer only insofar as that renders her capable of such vivid and at times scathing portraits. It seems like she’s erasing herself in favor of painting portraits of others, but she’s retelling their stories in her own words. She’s not repeating them verbatim.

Conversations with strangers on a plane occur early in two of the books, which sets the tone for the project. Why does that happen, people pouring their hearts out to strangers on a plane? Because it is a temporary space, because there is an intimacy borne of the close physical proximity, because the stranger will never be seen again, because there’s always a sense of mortality and powerlessness about being on a plane. There are other types of scenarios that inspire people to confide: the hairstylist’s chair (but in this case it’s the hairstylist who discloses), a gathering of writers, where there is almost a one-upmanship to prove who is the most damaged (and perhaps, then the more interesting writer?), a dinner with an old friend not seen in years, a writing workshop where students are willing to make themselves vulnerable. Sometimes the revelations by the speaker are unconscious, and only a careful listener (or reader) would pick up on the hypocrisy or self-deceptions that emerge from contradictory assertions.

But other times, the radically honest confidences are not in the context of any special relationship or setting, they just come. In the world of the trilogy, Faye is able to conjure this sort of atmosphere with, apparently, anyone she talks to. Faye usually omits the questions that lead to these radical disclosures from friends, and at times, near strangers. It’s fiction in that sense, a world more interesting than the one we inhabit. We aren’t usually privy to the questions she asks that makes the other person reveal the unutterable secret that holds their marriage together, the time they beat their children’s beloved dog, the assault by a stranger that made them unable to create. It’s an intense and double-edged fantasy, and certainly the fantasy of a writer.

I think Cusk, in her memoirs, and also in the character of Faye, takes on a hapless persona, a character who is always uncomfortable, but not afraid to express that discomfort, as if everyone should feel that way. She’s not afraid to be a bummer and I found this quality enchanting, the unapologetic quality of it. London is hostile, but Athens is too bright, the sunshine harsh and disorienting. For Faye, in the first two books, this discomfort comes from heartbreak, but heartbreak that goes deeper than the romantic kind. She, and her children, are survivors of the rending of their domestic life, the obliteration of certainties in the life the family had built together. In the first two books she is stumbling in the rubble, still obligated to tend to the needs of students, to men wanting an audience, to malicious neighbors, to her children, in this state of aftershock.

Funny

The grim tone is a foil to the funny scenes and could perhaps lead one to miss the humor. When Faye’s plane “neighbor, ” who has twice taken her out on his boat for a swim in the Greek heat, and who, with each of his monologues has revealed the straight-out lies he told about his two wives and himself, makes a pass at Faye, the action is startling and somehow hilarious. Maybe because we’re jolted to attention with live action actually taking place, as opposed to happening via a second- or third-hand account. But it’s also the description of the man’s advance itself, where she depicts him as moving like some kind of prehistoric caveman creature.

There’s also the scene in Transit, back in Britain, set in a posh country house, where a glamorous set of guests and their children have gathered, their complex troubles attendant, too. Faye’s gourmand cousin, who is peevishly trying to develop the children’s picky palates, sets down plates of tiny roasted fowl before all, and the children scream and weep at the dead little animals, candles blazing all around them, illuminating and flushing their faces like a painting. It’s a perverse and funny kind of climax near the very end of the book before Faye slips away from the mess the next morning.

Reception

I haven’t talked to anyone in person who has read the trilogy, though I’m frequently praising Cusk to reader friends, so maybe my proselytizing will lead to a chance to discuss it. In the meantime, I’ve read all of the reviews and profiles of Cusk online. The critical consensus seems to be that Kudos, the last book, is the culmination of the three. My theory is that this is because it’s the one that deals most explicitly with the publishing industry and its troubled marketing apparatus, with the fake and tedious aspects of the book fair, with the parrying done by writers at the after-panel dinners. It’s like how film critics love films about film-making and the film industry, the insider’s view of the process makes you feel closer to it.

But I think Faye/Cusk could make anywhere interesting – I remember starting Outline and being dazzled by how she made that familiar ritual of flight takeoff and the safety demonstration seem alien and new. And while it could be argued that Outline, too, is about the writing life (teaching a workshop), this is more the framework than the atmosphere or substance of the book, which are concerned with the sense of separation that comes from traveling, being away from home, taking in others’ pain. Faye is preternaturally sensitive while also standing behind glass. In Transit, the middle book, we see more of Faye because she’s at home. It’s full of a different tension. As she seeks to rebuild her life, most visibly by renovating dilapidated apartment, there’s an underlying anxiety about how quickly anything can be destroyed. Her monstrous downstairs neighbors, for example, befoul her attempts at starting fresh. The novel is full of shattered glass: the glass door at her hairdressers destroyed by a nervous boy slamming the door, the window of Faye’s car, which she has locked in the keys, smashed by her inconsiderate date, who wouldn’t wait to get his stuff. She must stand waiting with the car alarm wailing.

My favorite of the three was Outline, maybe simply because it was my first encounter with Cusk’s writing, but I think also because it so tangibly conveys the feeling of travel: the launch of the journey on the plane, the increasing sense of separation from home life, the intensity that weather, every new face and street corner takes on, because it is new, and because of the knowledge that it is all temporary.

There was a word in his language, I said, that was hard to translate but that could be summed up as a feeling of homesickness even when you are at home, in other words as a sorrow that has no cause. This feeling was perhaps what had once driven his people to roam the world, seeking the home that would cure them of it. It may be the case that to find that home is to end one’s quest, I said, but it is with the feeling of displacement itself that the true intimacy develops and that constitutes, as it were, the story. Whatever the kind of affliction it is, I said, its nature is that of the compass, and the owner of such a compass puts all his faith in it and goes where it tells him to go, despite appearances telling him the opposite. It is impossible for such a person to attain serenity, I said, and he might spend his whole life marvelling at that quality in others or failing to understand it, and perhaps the best he can hope for is to give a good imitation of it, as certain addicts accept that while they will never be free of their impulses they can live alongside them without acting on them. What such a person cannot tolerate, I said, is the suggestion that his experiences have not arisen out of universal conditions but instead can be blamed on particular or exceptional circumstances, and that what he was treating as truth was in fact no more than personal fortune; any more than the addict, I said, ought to believe that he can regain his innocence of things of which he already has a fatal knowledge.

From Kudos, by Rachel Cusk

I finished this last book in Cusk’s incredible “Outline” trilogy today, and I’m still pondering this passage. Faye is responding to a young interviewer who’s trying to persuade her that she would be happy if she lived somewhere sunny. Her response appears to be that the questing dissatisfaction that drives her shouldn’t be attributed to her personal misfortunes, and that it is not ultimately a quality that she can or perhaps even wants to reject. This follows on one of the central questions Faye/Cusk seems to be asking: What does suffering bring? What does it make possible?

This struggle to get the words out of my mouth took me right back to a year in my childhood when I did not speak at all. Every time I was asked to speak up, to speak louder, the words ran away, trembling and ashamed. It is always the struggle to find language that tells me it is alive, vital, of great importance. We are told from an early age that it is a good thing to be able to express ourselves, but there is as much invested in putting a stop to language as there is in finding it. Truth is not always the most entertaining guest at the dinner table, and anyway, as Duras suggests, we are always more unreal to ourselves than other people are.

Deborah Levy, from The Cost of Living