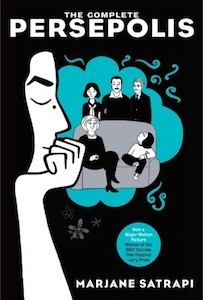

6. The Complete Persepolis (Pantheon, 2007, originally pub 2000-2003) – Marjane Sartrapi, trans.

I liked how this wasn’t a straightforward narrative of building a new life abroad after the political and social upheaval in Iran. There were difficult times and beautiful times in both places for the author, and ultimately, a sense of dislocation that has to be reckoned with no matter where she is. The tempestuousness and sometimes-shitty oblivious behavior of youth is all there, which I also appreciated. I liked the simplicity of the art, how much she does with black. Her family members are most vivid, visually – chic mother, gentle father, dashing uncle, feisty grandmother.

Origin: American Book Centre in The Hague

Fate: On the keeper shelf

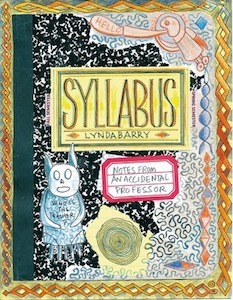

7. Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor (2012?) – Lynda Barry

Second time reading this, one of my favorite books discovered last year. I enjoyed this book more visually this time, Barry’s monkeys, her renderings of herself as Chewbaca. The generosity of a real teacher comes through in the exercises here, the enthusiasm for sticking to something and the best wishes for a breakthrough in thinking, or style, or habits.

Origin: American Book centre in Amsterdam

Fate: On the “always keep” shelf

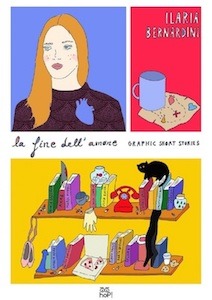

8. La fine dell’amore (2014) – Ed. Ilaria Bernardini

An anthology of 13 “graphic short stories” about the end of love. A big range, from sinister, to realistic, to funny, to dreamy and surrealistic. Strong enough visually that I could understand with my intermediate Italian. A beautiful collection. I’m also happy that I stumped Amazon.com with this pick! Only available on Italian websites. http://www.hopedizioni.com/la-fine-dellamore-graphic-short-stories/

Origin: A cool film-and-art-book store in Rome near Piazza Navona

Fate: On the “keeper” shelf

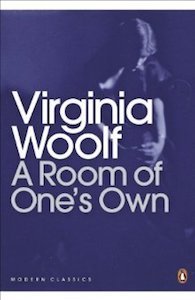

9. A Room of One’s Own (1929) – Virginia Woolf

I read this a long time ago in college. It made a big impression on my budding feminist self them, particularly the part about Shakespeare’s sister. This time I was struck by the depth and prescience of Woolf’s analysis, for example, her thoughts on the rarity of reading dialogue between two women, written to a woman, the novelty of it (Bechdel test anyone?); also her centering the argument on economic autonomy – the recognition of her own privilege and how that afforded her the freedom of time and space to create. I was also struck by her ability to view women as a separate economic class and in that sense assess their poverty and unpaid work at the time – such revolutionary thinking at the time (and still is, depending who you’re talking to). Also a pleasure to read, with her wit and balanced, intricate sentences.

Origin: The uninspired English bookstore full of remaindered titles in Leiden

Fate: Somewhere in the apartment? Just an easily replaced cheap paperback edition, so I’m not concerned

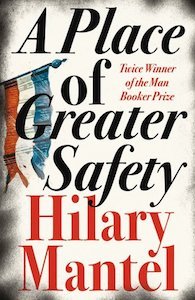

10. A Place of Greater Safety (2006) – Hilary Mantel

Mantel’s MASSIVE fictionalized account of the French Revolution, from the point of view of the revolutionaries. The characters really came alive, but I confess it became a bit of a slog in the last 200 pages.

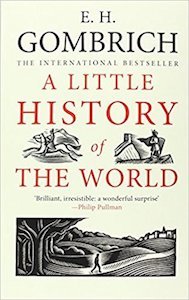

11. A Little History of the World (1935, trans. 2005) – Erich Gombrich

I think my whole feeling about this book would change with a change in the title to “A Little History of the West”. It’s intended for young readers, and it that sense it is refreshing and accessible, and comes from an art history perspective on European history, which always gives cause for hope.