The scales have tipped. The glass is overflowing. I’m not sure when the drop that caused the overflow happened, but it feels different now, the fact of women’s writing, women’s words in the world. As a child, a teenager in school, I felt the general tokenization of women. I received by osmosis (from textbooks, from teachers), the sense that “women writers” needed to be included in curricula to fill a quota, but that they weren’t quite as good as the writers that didn’t require a modifier (male writers).

Then, when trying to write, learning to write, there was the sense, also transmitted by teachers, anthologies, peers, that I should try to write to fit in with the men, to impress the men in the room, in the canon, at the publishers. Gradually, this fueled a rebellion and I wanted to read only women, discover women’s writing that wasn’t anthologized or talked about in institutions, and write like a woman (whatever that means, if anything). But this felt like a kind of isolation, marginalization in my reading and writing life. [The usual disclaimer: I’m writing from a mostly English-language, mostly American perspective…]

But the chauvinism isn’t a given now. The rejection of it is palpable! Women writers are becoming just writers, no modifier required. Joan Didion is the aspiration, not Norman Mailer. Women, who comprise the majority of fiction readers, now number among the critics. So many more varied women’s voices are being published, on a large scale, by major publishers, from mass market to literary. That’s not to say there’s still not a way to go, of course. This is the beginning and it feels great.

What’s struck me recently is that not only are new voices being published, but women writers from the past are being resurrected and appreciated. In the U.S., Eve Babitz, Lucia Berlin, Clarice Lispector, Elizabeth Hardwick, Penelope Fitzgerald, Renata Adler have all had a recent renaissance as major literary figures of the 20th century. (Parul Sehgal of the New York Times wrote an interesting piece about this phenomenon and paying attention to what caused the vanishing in the first place.) Not only was Zora Neale Hurston’s book on a former slave published in 2018, 90 years after it was written, it got a surprising amount of ink when it did (History.com, NPR, The Huffington Post, The New Yorker, The Daily Mail!).

I’ve been thinking of all of the Modernist women I skipped over in my education, whose work I still haven’t read. I was reading T.S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound hungrily, but skipped over Mina Loy, H.D. I didn’t know about Djuna Barnes, Kay Boyle, who were there all along, drinking and smoking with the dudes, and writing, too.

As someone with an interest but no particular expertise on visual art, I’ve been peripherally aware of a similar tendency in that realm, as well. I was delighted by Peter Schjeldahl decrying the title “Woman Impressionist” of the big 2018 Berthe Morisot show at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (“a great artist who is not so much underrated in standard art history as not rated at all”). There was the recent astounding Hilma Af Klint show at the Guggenheim. She was painting abstract forms in the early 20th century on her own, as part of a spiritual search, long before Kandinsky, and didn’t want to be shown in her time for fear of being misunderstood. There was Yayoi Kusama’s triumphant, late-career world domination, beginning with the blockbuster show at the Hirshhorn in 2017. A big Frida Kahlo show now at the Brooklyn Museum. Joan Mitchell’s work setting auction records. (I’d never heard of her before last year, but of course had heard of de Kooning and Pollock.) I’ve seen lots of Artemisia Gentileschi’s images pop up all over the Internet. Hopefully the art history books are being rewritten. These people, their work, have been there the whole time.

I don’t have the same evidence, but a sense or hope that this transformation–the recognition of women who were there all along, making history and culture–is happening in other areas, too, ones that I track less, like comedy, film, food, and science.

This resurrection of women from the past makes me think of an ancient civilization that’s discovered beneath the living city. It was there all along. We are excavating, removing the layers of dirt that was dumped on women’s work. We’re carefully lifting it up, dusting it, examining it, valuing it, attempting to connect it to other fragments. We’re realizing, too, what’s been lost and can’t be recovered.

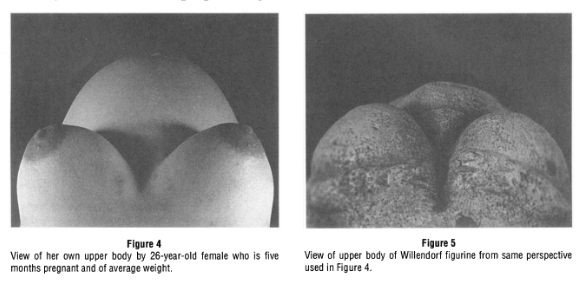

Evidence of this past civilization goes even further back. I don’t know why we’ve assumed it was only men drafting illuminated manuscripts, sculpting goddess figures, painting on cave walls, but we do, I do. We need scientific proof that it was possible women were doing these things, otherwise we don’t believe it, can’t picture it. I saw several articles making the rounds recently about flecks of blue lapis lazuli being found in the teeth of a 1,000 skull of a nun in a German monastery. It’s evidence that women, too, created beautiful illuminated manuscripts. There’s scientific proof that most cave paintings were done by women. And there’s the theory that “the first images

of the human figure [fertility goddesses] were made from the point of view of self rather than other” and “Paleolithic ‘Venus’ figurines represent ordinary women’s views of their own bodies.”

The uncovering of women’s part in our civilization and culture isn’t a physical discovering. It’s been there all along. We covered it up and made ourselves blind to it. We have to remove the layers of dirt from history books, museums, our own minds and consciousness…

mother and coming to terms with her feelings about her mother in psychotherapy. I could see how its “meta-book” quality (she talks about the process of writing the book in the book) and its focus on her therapy (many pages are panels of conversations with her therapists) would not appeal to everyone, but I felt very open to it & interested in it. She touches on a lot of my own interests – the theories of Dinald Winicott, the life of Virginia Woolf, the psychoanalytic process. Bechdel’s persona, a curious, creative, insecure, unrelentingly honest artist and memoirist is also highly sympathetic.

mother and coming to terms with her feelings about her mother in psychotherapy. I could see how its “meta-book” quality (she talks about the process of writing the book in the book) and its focus on her therapy (many pages are panels of conversations with her therapists) would not appeal to everyone, but I felt very open to it & interested in it. She touches on a lot of my own interests – the theories of Dinald Winicott, the life of Virginia Woolf, the psychoanalytic process. Bechdel’s persona, a curious, creative, insecure, unrelentingly honest artist and memoirist is also highly sympathetic.

Young American poet in Madrid. Some say this is thinly disguised autobiography – I found myself actually not being that curious either way, which is not always the case. I really liked the internal quality of the novel, the absolute subjectivity. You get the feeling that the people the narrator interacts with actually like him better and think he’s smarter, more interesting & socially adjusted than he gives himself credit for (doesn’t help that he’s high & paranoid most of the time). I also loved the way he described the fog of living in a country where you halfway speak the language, how you have multiple interpretations for what someone could be saying to you, and how all of those versions might be wrong. My only quibble was with the ending, it’s all tied up into a neat bow, not sure what we as readers are intended to be left with. (I passed it along to a friend, not a keeper on the shelf, but worth passing along.)

Young American poet in Madrid. Some say this is thinly disguised autobiography – I found myself actually not being that curious either way, which is not always the case. I really liked the internal quality of the novel, the absolute subjectivity. You get the feeling that the people the narrator interacts with actually like him better and think he’s smarter, more interesting & socially adjusted than he gives himself credit for (doesn’t help that he’s high & paranoid most of the time). I also loved the way he described the fog of living in a country where you halfway speak the language, how you have multiple interpretations for what someone could be saying to you, and how all of those versions might be wrong. My only quibble was with the ending, it’s all tied up into a neat bow, not sure what we as readers are intended to be left with. (I passed it along to a friend, not a keeper on the shelf, but worth passing along.) horoughly enjoyable if you disregard her lofty claims for the book. Namely, that it’s a sorely needed feminist treatise on pop culture & the everyday conundrums of femininity (such as what to wear). Especially if Lady Gaga is the absolute height of feminist achievement (as she claims, ugh). There’s in fact extensive writing & thinking on this stuff all over the internet (though maybe not written by someone of her generation).

horoughly enjoyable if you disregard her lofty claims for the book. Namely, that it’s a sorely needed feminist treatise on pop culture & the everyday conundrums of femininity (such as what to wear). Especially if Lady Gaga is the absolute height of feminist achievement (as she claims, ugh). There’s in fact extensive writing & thinking on this stuff all over the internet (though maybe not written by someone of her generation). Fascinating account of the lifelong relationship between Simone de Beauvoir & Jean-Paul Sartre, spanning their complicated private lives, literary works and the great wave of the 20th centruy. This was my second read, otherwise would be higher on the list – my first read transformed my perspective for a while.

Fascinating account of the lifelong relationship between Simone de Beauvoir & Jean-Paul Sartre, spanning their complicated private lives, literary works and the great wave of the 20th centruy. This was my second read, otherwise would be higher on the list – my first read transformed my perspective for a while. -Absolutely absorbing. He plants information masterfully, weaves the story in a way that keeps you reading (from the first sentence you know there’s a downfall to come). Franzen sticks to his mantra of being a friend to the reader – a feat to create a literary page-turner.

-Absolutely absorbing. He plants information masterfully, weaves the story in a way that keeps you reading (from the first sentence you know there’s a downfall to come). Franzen sticks to his mantra of being a friend to the reader – a feat to create a literary page-turner. passing into stone and leather, as if to acquire a statue’s quality. The slightest wilting is tragic in women because we make it so. A woman’s skin has to rival the flower, her hair has to retain its buoyancy, aging does not constitute a new kind of beauty, hierarchic, gothic, classical. She can only seem incongruous, condemned, doomed among the silks and the flowers and the perfumes and the chiffon nightgowns, the white negligées. Why can she not efface her rivalries behind black gowns as the Greek women, as the Japanese women do? It is the rivalry among the elements we associate with women which prevents the transition to some other kind of beauty. Caresse Crosby gave me a shock when she appeared in a bright deep red dress, a buoyant dress, frou-frou, walking lightly on very high heels, but then her face appeared like a ruined mural, eroded with time. The powder and the lipstick did not adhere to its dryness but seemed about to crumble off. The sadness was that not all of Caresse aged simultaneously; her voice and laughter were younger […]

passing into stone and leather, as if to acquire a statue’s quality. The slightest wilting is tragic in women because we make it so. A woman’s skin has to rival the flower, her hair has to retain its buoyancy, aging does not constitute a new kind of beauty, hierarchic, gothic, classical. She can only seem incongruous, condemned, doomed among the silks and the flowers and the perfumes and the chiffon nightgowns, the white negligées. Why can she not efface her rivalries behind black gowns as the Greek women, as the Japanese women do? It is the rivalry among the elements we associate with women which prevents the transition to some other kind of beauty. Caresse Crosby gave me a shock when she appeared in a bright deep red dress, a buoyant dress, frou-frou, walking lightly on very high heels, but then her face appeared like a ruined mural, eroded with time. The powder and the lipstick did not adhere to its dryness but seemed about to crumble off. The sadness was that not all of Caresse aged simultaneously; her voice and laughter were younger […] their character and women for the dewy, ephemeral quality we call beauty were still enforced.

their character and women for the dewy, ephemeral quality we call beauty were still enforced. I have now known community living. But I am still convinced that these people who are so proud of giving birth and raising three children are giving less to the world than Beethoven, or Paul Klee, or Proust. It is their conviction of their virtuousness which distresses me. I would like to see fewer children and more beauty around them, fewer children and more educated ones, fewer children and more food for all, more hope and less war. I was not proud at all of having helped three children with faces like puddings or oatmeal to live through a Sunday afternoon. I would have felt prouder if I had written a quartet to delight many generations.

I have now known community living. But I am still convinced that these people who are so proud of giving birth and raising three children are giving less to the world than Beethoven, or Paul Klee, or Proust. It is their conviction of their virtuousness which distresses me. I would like to see fewer children and more beauty around them, fewer children and more educated ones, fewer children and more food for all, more hope and less war. I was not proud at all of having helped three children with faces like puddings or oatmeal to live through a Sunday afternoon. I would have felt prouder if I had written a quartet to delight many generations.