15. Peggy Guggenheim: Mistress of Modernism by Mary Dearborn (Virago Press, 2004)

A sympathetic biography of Peggy Guggenheim, who was certainly smarter and suffered more than anyone gives her credit for. An amazing life filled with giants of the 20th century: she received moral support from Emma Goldman when deciding to leave her abusive first husband, had intense affairs with Samuel Beckett and Max Ernst (etc.), and a deep, complicated friendship with Djuna Barnes, among many others. Dearborn is perhaps too sympathetic at times, glossing over Guggenheim’s difficulties being a mother to her troubled daughter Pegeen, and not delving too deeply into her sexual compulsions. (I think Peggy’s often unfairly derided for her active sex life, when in a figure like Jackson Pollock it’s depicted as a sign of power and vigor, but this did veer into compulsive behavior, by her own admission. Dearborn attributes the bad press to Guggenheim’s own outrageous autobiography, which she sees as a mistake in some ways.) Fair enough, Dearborn is seeking to tip the scales of history more in Guggenheim’s favor, and perhaps felt she had to overcompensate a bit, given the reams of bad press over time…

Provenance: Impulse buy at the gift shop at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao

16. Kiki’s Memoirs by Alice Prin, trans. (Ecco, first published 1929)

I’ve long been intrigued by Kiki of Montparnasse (born Alice Prin), who was muse and model to many artists in 1920s Paris, most notably Man Ray, and generally the life of the party (Queen of Montparnasse). This is a translation of her memoirs, published in 1929 when she was still young. (The original hipster snob Hemingway says in the introduction that it’s a crime not to read them in French, and undoubtedly her voice must be much distinct and charming en francais.) She tells of her poverty-stricken origins in the country, and surviving many difficult jobs in Paris before finding her home in bohemia. She comes off as self-deprecating, resilient, and fun. This edition includes lots of photos and Kiki’s own paintings.

Provenance: Ordered from Better World Books

17. Little Labors by Rivka Galchen (New Directions, 2016)

A slim, sort of uncategorizable book, inspired by Shei Sonagon’s The Pillow Book. Written in snippets, Galchen documents her daughter’s babyhood and new motherhood, mixed with musings on babies in literature, awkward encounters with her neighbor, etc. A fun read. I love an uncategorizable book.

Provenance: Van Stockum bookstore in Leiden (RIP)

18. My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (Jonathan Cape, 2018)

I was impressed by how Moshfegh pulls off the conceit: a beautiful, wealthy intelligent depressed young woman decides to drop out of life and spend a year in her apartment knocked out by sleeping pills and other drugs. Moshfegh somehow spun an entertaining novel out of this. There are some really funny moments, and sometimes the meanness of this character is a too-brutal sting. Once I finished it, though, and still many months later, I’m left casting around for the larger thoughts or point of the work, for example, the inclusion of 9/11 (and maybe there doesn’t have to be one?), but I feel like I missed something.

Provenance: The American Book Center, The Hague

19. Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill (Vintage, 2014)

I wish I had come across this novel pre-hype. I think I’d read too many giddily besotted endorsements to give it a fair shot. (Offill’s new book, Weather is just out and also receiving big praise.) This book is loved because it explores art-making and its sometimes uncomfortable coexistence with marriage and motherhood, with wit and smarts in a collagey-form (that brings in, for example, facts about astronomy). I loved the first third , as a wonderfully distinct character and voice is established from the start, but I lost this sense by the last third or so, when it devolves into a story of a marriage attempting to survive infidelity, which was less interesting. No fault of the author, but the (white) Brooklyn-ness of it all put me off a little, and I also say this as a former long-time resident of gentrifying Brooklyn.

Provenance: Bought new at The American Book Center, Amsterdam

20. Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn (Broadway Books, 2012)

I have a bad habit of taking challenging books with me when I travel, thinking I’ll have uninterrupted time to focus on them on the plane, and in downtimes during family visits, etc. I then often end up avoiding the book because I’m jet-lagged, or overstimulated/tired from exciting travel and time spent with loved ones I don’t see often, etc. and cart them around for nothing, and then end up buying other, easier books on the trip. This December I decided not to take any books with me, but the plan backfired. I ended up casting around for something to read in rural Virginia where we were staying and went searching in the nearby free book library. Gone Girl was perfect – funny, fast-paced, not too cerebral to pick up between activities or before bed. I’d seen and enjoyed the movie and was curious about the full “cool girl” monologue. Aside from the obvious success of the page-turner aspects of the novel, Flynn wrote a believable dude character, and also captured a particular post-recession time.

21. Topics of Conversation by Miranda Popkey (Knopf, 2020)

An impressive and ambitious debut novel, a work exploring ideas about women and power. I said more about it in a review for The Chicago Review of Books. In the review, I didn’t mention some of my lingering questions about its success as a work of fiction, as I wasn’t able to articulate them clearly, and it would have been unfair to include them. Essentially, I wasn’t convinced by the narrative voice, the reality of the narrator, her self-loathing and scorn for kindness. There are works of fiction that grab me from the first line, I’ll go anywhere with the narrator, and other times I don’t trust the fiction and keep my distance, I become skeptical about every claim; this book was right on the cusp of this line, I was never fully won over as a reader. I’d like to get better at identifying, understanding and writing about whatever magic a writer employs to make a voice “real” in this sense (both in works of fiction and nonfiction). Obviously, at some level, this becomes a question of taste, but still…

Provenance: Galley copy from the publisher

22. Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A.

by Lili Anolik (Scribner, 2019)

This sort-of biography is interesting insofar as Eve Babitz is fascinating, both her wild life and inventive work. Anolik warns in the first chapter that she won’t even feign any distance or objectivity about her subject, and generally approaches her material in her capacity as the fanatical president of the Eve Babitz Fan Club. It’s the maximum expression of the worst possible interpretation of the permission New Journalism gave writers, the centering of the journalist herself in the story.

Anolik was instrumental in reviving interest in Babitz (which eventually led to her work coming back into print) via a feature she wrote for Vanity Fair in 2014 after many years of pursuit, and while she deserves credit for this accomplishment, she sees it as giving her unique ownership over Babitz’ life and work. In the end, she does Babitz a disservice, as an authoritative biography (which she seems more than capable of as a researcher and writer) would have done much more for Babitz’ legacy than a book filled with Anolik’s opinions about key events and figures in Babitz’ life, including Joan Didion and Jim Morrison, whom she trashes. Most surprising, and disappointing, was Anolik’s curt dismissal of Babitz’ novels as essentially not worth reading. This is OK, though, Anolik explains in a digressive lesson on the history of literature, because the novel is dead, anyway… I would recommend this only to established readers of Babitz, otherwise best just to begin with Slow Days, Fast Company and go from there.

Provenance: Bought new at Spoonbill & Sugartown, Brooklyn

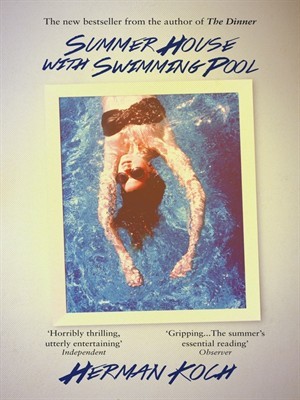

23. Summer House with Swimming Pool by Herman Koch (Atlantic, 2015, first published 2011)

A suspense novel by the Netherlands’ best-known fiction writer, featuring a gratuitously unlikable narrator. I could have maybe forgiven the gross views espoused by the protagonist if the novel as a whole had held up plot-wise, but the story kind of collapses in on itself. I will say that Koch is good at writing tension. I wrote more about this novel here.

Provenance: Clearance sale at Van Stockum bookstore, Leiden (RIP)