I found myself re-reading several favorite books last year, especially in the beginning of the year. This wasn’t a deliberate decision; I think was a way to find direction (the direction of my thoughts, writing, way of thinking). It’s also a heartening confirmation that I’m not keeping all of these books, carting them across oceans and to different apartments over the years for nothing – I will get back to many of them…

I haven’t included these in my ranking as it’s not fair to the books read for the first time, and it’s also impossible to determine any sort of preference among these – I value them all, but often for very different reasons. Five re-reads listed below in the order read.

RE-READ

Things I Don’t Want to Know by Deborah Levy (Notting Hill Books, 2013)

Playwright and novelist Levy’s account of her “origin story” as a writer, a response to Orwell’s essay “Why I Write.” It’s short, honest and powerful. This was my second read. I fell in love with this book in 2017.

The Lover by Marguerite Duras (Pantheon, first published 1984)

This was my third or fourth time reading this novella. It’s a guiding light of what can be accomplished in some 120 pages. Incredible compression, a whole life. My first read, I was around 20, and I was impressed by the assurance in the narrative voice and stunned by single paragraphs at a time, which were like incredible poems (the paragraph describing the narrator’s unstable mother attempting to raise chickens, the house falling into ruin, for example). The second time I realized how much it was a devastating love story about her mother, more than about the older man. This time I was more aware of Duras’ autobiography in the work, the kind of strength and defiance it takes to write through pain in this way. Again amazed by the authority in the voice, how I wouldn’t question it despite the drama (melodrama?).

I’ve been thinking about literary works I can’t “recover” from – their initial impact is so great, it’s hard to move beyond them to other works by the author. I just want to re-read the one, swim around in it, never move on. (Rather than happily diving into their whole oeuvre, which happens with other works.) This is one of those books. I own a couple of other novels by Duras but haven’t touched them, but maybe it’s time.

Susan Sontag: The Complete Rolling Stone Interview by John Cott (Yale University Press, 2013)

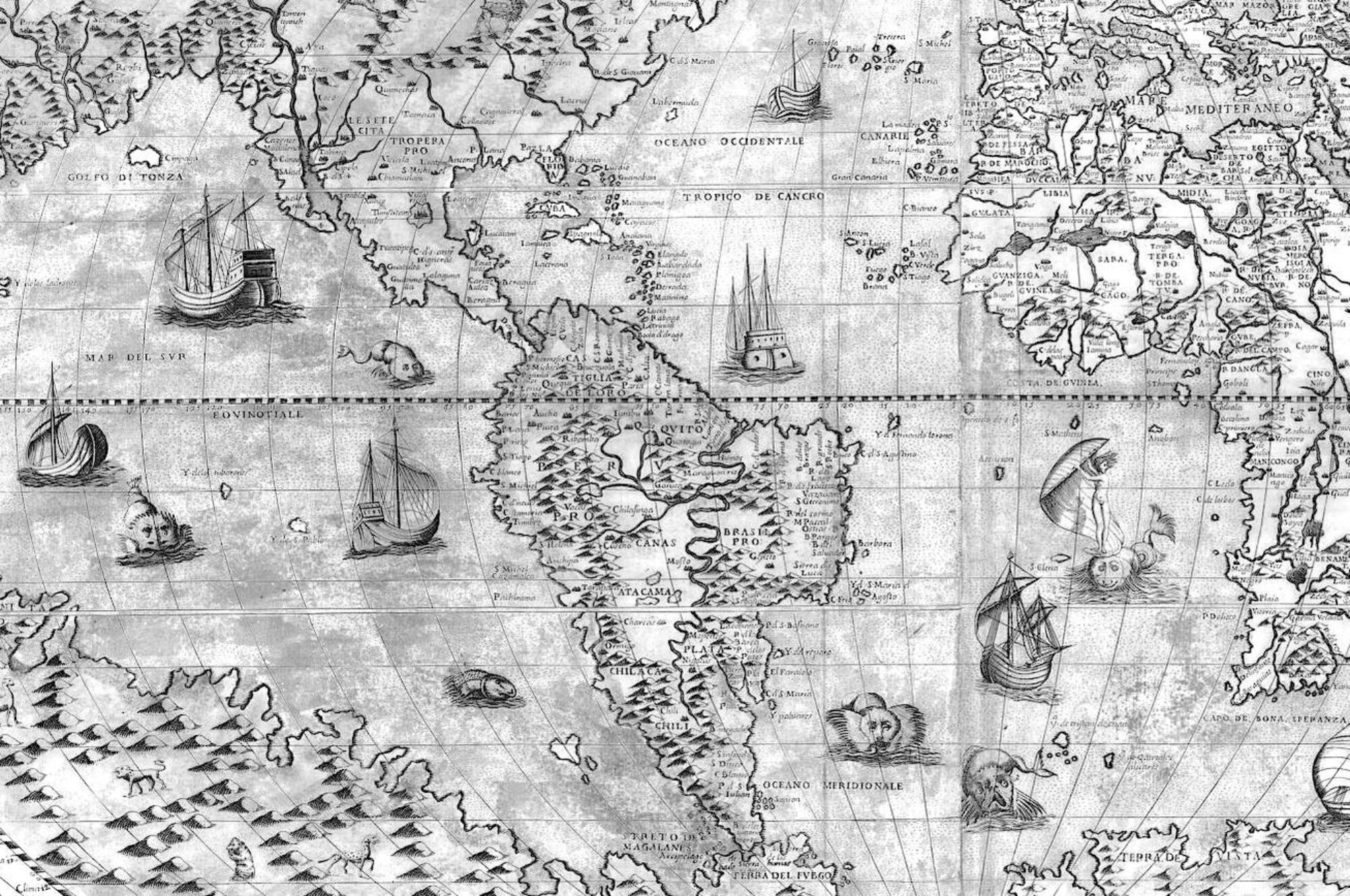

This book-length interview is bursting with ideas and questions from genius Sontag, it could certainly be read multiple times. The thought that stuck around with me this time is Sontag’s insight into the fragment – why the fragment is so compelling to us. It’s a sign of an old civilization, where so much has accreted that a fragment (whether visual or textual) can resonate with so much meaning… More thoughts on this book when I last read it in 2017.

Speedboat by Renata Adler (NYRB Classics, 2013 reprint, first published 1976)

You could carve at least two completely dazzling prose poetry collections out of this experimental novel. Adler puts some lazy poets to shame by collecting all of this inventive, delicious prose into a single work. And it is indeed a novel, not in an explicit way, but there’s a protagonist, you get a sketch of her biography, her love life. It’s atmospheric – a paranoid, hung-over, sweltering, wayfaring existence in New York in the 1970s.

Anecdotal, minor gossip digression: I was lucky enough to see Adler at the Center for Fiction in 2014, when she had her big comeback and NYRB reprinted her work. She was shy and self-deprecating. Eileen Myles was in the audience and during the Q&A she essentially asked Adler why she was apologizing herself, took issue with her self-effacing manner. I didn’t really think about it till I got home, as I was excited that Eileen Myles was even there, but it dawned on me that Renata Adler should be allowed to talk however she wants, what kind of question is that?…

Also, when I went up to get my books signed, Adler said my name looked like the word “begin,” and signed them “To Begin–” which I love.

My Life in France by Julia Child and Alex Prud’homme (Knopf, 2006)

I think I picked this up to feel better last summer. Julia Child reminds you about everything that’s great about being alive, or maybe she makes everything about being alive seem great — travel, eating, marriage, work. That’s what struck me about this read, her supreme dedication to her work, her gratitude for discovering what she really loved to do. I also realized on this read that maybe classic French food is not for me, either to eat or cook — so rich, so meaty, so many organ meats, so many elaborate preparations…

ABANDONED

The Waves by Virginia Woolf

Woolf’s fiction is a big gap in my reading; I’ve only read Mrs. Dalloway (which was and remains important in to my reading/writing life). I must confess I abandoned The Waves just a few pages in, not because of the stream-of-consciousness style, but because it immediately introduces six characters who alternate speaking on every line. Many names on pages 1-2 immediately puts me off a book. I’ll have to return to this when my mind is calmer, maybe in like 20 years or so…