6. Transit and 7. Kudos by Rachel Cusk (Faber & Faber, 2016 and 2018)

Books two and three in Cusk’s brilliant trilogy. I’ve placed them together as I read the around the same time and they’re not entirely distinct in my mind. Transit gets us closer to Faye in her home territory of London, while in Kudos she’s on the road again, at a couple of book festivals, with much to subtly say about the publishing industry, other writers, etc.

Nearly a year on from reading them (and thinking of them in the midst of the global pandemic and economic crisis) I do wonder what’s left, they seemed so of the time, and now we are clearly in a new era… I think a lot of the thrill and satisfaction comes from the writing itself – Cusk is just absolutely dazzling and gets straight to the emotion heart and complexity of any situation. I wrote more a lot more about this trilogy here.

Provenance: Probably The American Book Center in Amsterdam?

8. Peregrinos de la belleza: Viajeros por Italia y Grecia by María Belmonte (Acantilado, 2015)

A nonfiction account of writers, artists, scientists from Northern Europe who found their true home in Italy and Greece, whether because of a love for ancient art, that Mediterranean light or the allure of the perfect island. Each subject covers a different “pilgrim of beauty” (all men) and span the 18th century (beginning with the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann) to 20th century (ending with writer Lawrence Durrell). Belmonte is a charming guide, clearly in love with the Mediterranean herself, and generous to her subjects (overlooking their major deficiencies as husbands or fathers, for example), focusing on their creative output and inspiration drawn time in Italy and Greece. I also get dreamy about those countries, so this was a nice escape in the winter months.

Provenance: the fantastic Panta Rhei bookshop in Madrid, which specializes in art, design and travel books.

9. Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino (Fourth Estate, 2019)

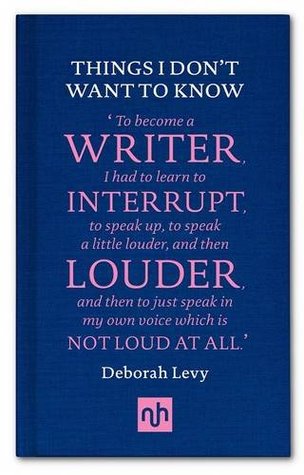

I, like many other admirers of Tolentino’s writing in the New Yorker, couldn’t wait to get my hands on this essay collection. I was absolutely blown away by the first essay, about our life on the internet, framed by her personal experiences online, which began when she was a child (Tolentino was born in 1989). I also enjoyed her piece on the “marriage-industrial complex.” Less a fan of the essays on her experiences with religion and ecstasy (the drug), and on women in fiction. If I’m allowed a quibble with the book, I think several of the pieces were long-winded and unfocused at times (I learned more than I ever wanted to know, for example, about ballet barre classes), which is maybe evidence of the value of being rigorously edited at a major publication. But a minor quibble. It’s a pleasure, actually to see a young woman writer take up this much space, embrace her success, follow her thoughts to the end and beyond, and it also shows she has room to grow, which is exciting.

Side note on the culture buzz around this: The reception and Tolentino’s perfect book tour and media blitz became a story itself because many of her essays touch on how our current incarnation of capitalism (of life lived online) ultimately exploits what’s unique and intimate about the self, with Tolentino consistently admitting her complicity and inability to escape the web, both in interviews and in the book. I think there’s a touch of envy to the criticism, because Tolentino is successful in every way – brilliant, talented, also young and beautiful, funny, self-deprecating, and also seems like she’d be fun to hang out with. You have to just give in and love her.

Provenance: American Book Center in The Hague.

10. Open Secrets by Alice Munro (Vintage, 1994)

I didn’t start reading Munro until about eight years ago, and began with her most recent work (thanks to my lovely mother-in-law who introduced me to her). So it was interesting to pick up some of her earlier stories. The collection as a whole isn’t the 100% masterpiece that Hateship, Friendship, Loveship, Courtship or Like Life are, but Munro will always offer something memorable, no matter what the story. I tend to like her historical stories less than the ones set in modern times. There were a couple in this collection that really stuck with me, though, “The Albanian Virgin”, about a woman traveler kidnapped by an Albanian tribe, and “The Jack Randa Hotel”, about a woman who goes to Australia in secret in pursuit of the man who left her. (The opening of the latter story, when a plane lands and is doused with insecticide before disembarking, even made it into my dreams.)

Provenance: Boekenzolder (free book warehouse!)

11. After Henry by Joan Didion (Vintage, 1992)

A lesser-known essay collection by Didion, published in the early 90s. Maybe forgotten because it’s frontloaded with topical essays full of names most wouldn’t recognize now (e.g. Reagan’s former chief of staff) and insider-baseball observations about the political class. But it has a couple of stunners that make this worth owning: a profile of Patti Hearst, and a magisterial, long piece about the Central Park Five, which turns into a portrait of New York City in the 80s, the hierarchies, the media, the governance, the collective self-delusions shared by city dwellers. A real model for the form.

Provenance: Boekenzolder (free book warehouse)

12 . Coventry by Rachel Cusk (Faber & Faber, 2019)

This is a collection of Cusk’s essays previously published in various places, so not a cohesive work, which I was disappointed to discover. Still, she’s incredible on just about any subject, including art – Louise Bourgeois, for example. The essay on her teenage daughters, called “Lions on Leashes” is also wonderful. I guess this book is a bit further down my list because a few of the opening pieces struck me as absurdly cranky – one about traffic in her small town in the countryside (or maybe I’m the cranky one – I have no interest in reading about driving as a metaphor). That being said, Cusk has set the bar ridiculously high, so one can’t really justifiably be critical about any of her work.

Provenance: The American Book Center in Amsterdam

13. Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit by Aisha Sabatini Sloan (1913 Press, 2017)

This book made me realize that an essay collection is a bit like a short story collection: the author is trying out different techniques and ways in, the essays will vary in length and topic, some will be more successful than others, and there are ones you’ll like more than others. This collection had many “braided” essays – ones that weave in often seemingly disparate topics (growing up African American in L.A., the art of David Hockney, and Rodney King). She covers a lot of ground in this book: her white cousin’s experience as a cop in Detroit, the art of Basquiat, Buddhist meditation, Beyonce’s Lemonade, body memory, especially as an African American (a history of bodies subject to violence), the 2016 election … My favorite was an essay as list form about Sabatini Sloan’s father, renowned photographer Lester Sloan, which successfully employs the second person. I like her voice best when she’s ironic, funny, personal.

Provenance: Ordered direct from the publisher (my lovely publisher), 1913 Press.

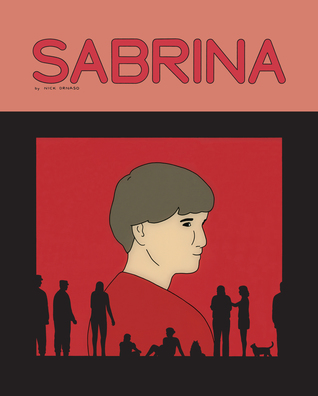

14. Sabrina by Nick Drnaso (Drawn & Quarterly, 2018)

I got interested in this book when it became the first graphic novel ever to be nominated for the Booker Prize. The sound bite attached was that it’s the first book to successfully convey the Trump era. I’m not sure about that claim, but I do agree that it conveys people in places in America you don’t often see represented in fiction. The art is surprisingly simple, dull at times, even, which I think critics of the book objected to. But I think this is a conscious choice, a way to contain the grief, paranoia, disconnection of the characters. The worst events happen “off screen,” which I think places the moral responsibility, the weight of reaction on the reader… Still thinking about this one. I think I need to read it again.

Provenance: Ordered from the local comics store.