My round-up of “last year’s books” is coming a bit late as I’ve turned this annual tradition into quite the project, and I was busy writing book reviews. I decided to go ahead and finish it, as I mostly post this for my reader friends, and it doesn’t really matter when I get it up.

My round-up of “last year’s books” is coming a bit late as I’ve turned this annual tradition into quite the project, and I was busy writing book reviews. I decided to go ahead and finish it, as I mostly post this for my reader friends, and it doesn’t really matter when I get it up.

I love seeing other people’s book lists, friends and strangers alike, and I’m always so curious to see what someone is reading (on the bus, on their shelves). I started this annual round-up because I wanted to understand what I actually thought about a book, how much of it remained, and what my reading life as a whole amounted to. I decided to post it online (on a defunct anonymous book blog) so that I would complete the thought and actually finish the exercise. Then it became a way of sharing with my bookish friends scattered around the world, who I miss talking to. They’re not quite reviews, as I think a book review actual owes more to both the readers and writer (I hate summarizing plots, for example). Just a few thoughts.

As usual, the ranking is not necessarily based on literary excellence, but on how big an impact the book made on me (sparking new thoughts, feeling things, the lingering image); how likely I am to press it into a friend’s hand; how much of it remains months after reading it.

A note on book lists

Seeing all of the best of the year, best of the decade, best of the 21st century book lists at the end of 2019 wasn’t as fun as I’d anticipated. After these lists came the raft of lists most anticipated books of 2020. All of the lists started to feel like this endless, churning mass, or like a crowded conveyor belt of text that’s impossible to keep up with. Obviously this exclusive focus on what’s new is what keeps the publishing industry viable, but it must also be so disheartening for anyone who published a book 3 years ago, or 7 years ago, or 15 years, this feeling of only having a couple of months to make an impact.

I do love discovering a bold and new voice, who is speaking to our precise moment. But there should also be at least a little room in our shared cultural spaces (book coverage in newspapers, book sites like Electric Lit, etc.) to consider work beyond the months (weeks?) of its big debut… I saw some conversations around this on Twitter, with writers/critics attributing this myopic focus to the loss of dedicated book sections in newspapers, well paid book review gigs, etc. Books coverage being reduced to the “listification” of writing about brought by the internet.

It’s sad to lose some of the excitement around new book lists to this general sense of information overload I’ve been trying to keep my head above for the past few years. On the other hand, it’s less pressure to keep up, and maybe make my reading life more intentional.

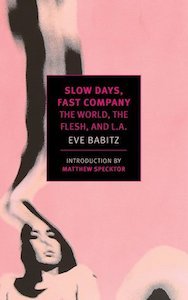

On the subject of reading books other than what’s hot now, I’ve noticed that, since I began tracking my reading more closely, beginning in 2009, besides reading newish books I’m excited about, I’ve also kept up a steady parallel stream of books published by women in the 1970s. This wasn’t intentional. I think it’s partly because one writer leads me to another (e.g. Mary McCarthy led me to Elizabeth Hardwick), the fact that there’s been a revival of these writers in recent years who criminally went out of print (Renata Adler, Eve Babitz). I also think it’s because the 1970s were a time of intense, deep-thinking creative production, also in film and music. (The possible reasons why are whole other post.))

Overview

I read 33 fiction, nonfiction and poetry books. This number is higher than usual, I think in part because I broke up with The New Yorker in the spring (it’s an up-and-down relationship) and because I tried to get a grip on my social media addiction.

General trends in my reading life in 2019: Lots more nonfiction, mostly essay collections; lots more poetry read cover-to-cover rather than dipped in and out of; a decline in my reading of books in translation and books written in other languages, which I’m not happy about. I also felt a need to re-read books I’ve loved, so I’ve listed these last, as I’ve written about them at other times.

A few stats on the books I read:

- 45% were non-fiction (mostly memoir/personal essays, also art/literary history, biography), 39% fiction (mostly novels), 15% poetry

- 81% were by women, 19% by men (out of 31 total writers)

- Authors were from the U.S.A. (18 or 58%), United Kingdom (4), France (2), Netherlands (2), Canada, Germany and Spain (1 each)

- I read 32 books in English, 3 of which were in translation, and 1 book in Spanish.

- 61% of the books I read were published in the past 10 years, 31% before 2010, 12% in the 1970s. Original dates of publication span 1929-2019.

- 18% were rereads, 15% were by Rachel Cusk 🙂