6. The Lost Daughter by Elena Ferrante, trans. Ann Goldstein (Europa Editions, 2008, original 2006)

Ferrante’s last short novel before embarking on the Neapolitan quartet. The seeds of that project are planted here – a woman trying to make sense of her life after her daughters have grown up and left home. There’s a tension throughout as she watches a Neapolitan family on the beach every day, relating to a woman playing with her daughter, and also sensing the violence that could erupt when the patriarch is around, a tension that increases as she becomes involved in a strange way. A visual theme emerges of dark insects marring a picture-perfect scene (a black moth in a seaside bedroom, a worm coming out of a doll’s mouth) that seem pointed and unflinching, like much of Ferrante’s work.

7. Susan Sontag: The Complete Rolling Stone Interview by Jonathan Cott (Yale University Press, 2013)

A full transcription of a multi-part interview Cott conducted with Sontag in 1978, which was only excerpted at the time. (It ends up stretching into a book of 130 pages!) Sontag seems fun, and funny, via this interview. She admits her own contradictions, because of her commitment to constant change. She talks about how rock and roll (Bill Haley and the Comets), the energy of it, made her change her life and find the one she actually wanted to live in the late 50s (leaving her marriage and the academic life behind). They toss around fascinating takes on stuff like: how and why the fragment speaks particularly to our time; what is a miracle; why ritual require silence; loving both “high” and “low” art; being fundamentally Californian or East Coast; how people want to drift towards (over)simplifying, and why complexity has to be kept alive, etc…

8. Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City by Russell Shorto (Vintage, 2013)

This was a fun history of the city – not comprehensive, as the title indicates, but rather exploring the roots of Amsterdam’s liberalism, in the widest sense of the word (including capitalist enterprise, for example). The author pipes up with his own opinions and as a character, in a way, in the history he’s telling. This personal authorial intervention isn’t too obnoxious, but I wouldn’t say is entirely necessary either.

9. Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (Riverhead, 2017)

This novel was definitely written in response to the migrant crisis, and I liked how he pushed it into a speculative space of new possibility, rather than simply reflecting the depressing present. I had some minor quibbles – the epilogue, for example, which I had to pretend didn’t exist, the book ended so well otherwise. I also wondered at his very deliberate choice to keep his protagonists from being specifically Syrian or Muslim (although based on the details they might as well have been described as such). I guess this was underscore their “everyman-ness,” but in a way, it has the opposite effect. It would have been a strong statement to have “openly” Muslim characters in a novel with a largely Western readership, especially when every other location and character was grounded in specifics (named cities and nationalities). I remember a beautiful passage about what prayer meant, and had meant over time, to the more devout male character, for example, that made me understand Muslim prayer better. Anyway, a powerful novel, and I’m glad it’s gotten a lot of attention and people are reading it.

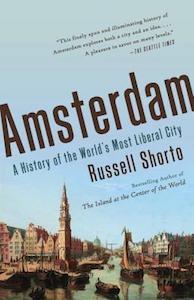

10. A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit (Canongate, 2005)

Essays on what it means to get lost, both purposefully (like Baudelaire in the city), and unintentionally, as a Spanish explorer separated from his group in pre-conquest America, and what you find when you’re found. Lost in a color, as Yves Klein, lost in another person. Solnit’s a phenomenal writer. I think she’s stronger when she writes about subjects other than herself (and she mostly doesn’t write about herself), perhaps because she maintains a final filter, a reticence to fully reveal her personal life. My favorite essay was on Cabeza de Vaca, and her own re-telling and re-contextualizing of what the “new world” was when the Spanish arrived, and how they missed it altogether. I love the way she is open to any subject, draws connections, and parallels. Her curiosity and love of history, art, anthropology, fiction, film, etc. etc. is invigorating. (She is also one of my favorite activist voices at the moment – everyone should follow her on FB.) I’ve read a lot of her work online, but this is the first book of hers I’ve read, and I’m excited there are many more to eat up.