Well, fuck the plot! That is for precocious schoolboys. What matters is the imaginative truth, and the perfection and care with which it has been rendered. After all, you don’t say of a ballet dancer, ‘He jumped in the air, then he twirled around, et cetera …’ You are just carried away by his dancing.

Stunning prose by Patrick Leigh Fremor

Reading A Time of Gifts and struck by the music and imagery of many passages.

Before he boards the ship taking him from London to Holland, to begin his journey:

“…Beyond the cobbles and the bollards, with the Dutch tricolor beating damply from her poop and a ragged fan of smoke streaming over the river, the Stadthouder Willem rode at anchor. At the end of lengthening fathoms of chain, the swirling tide had lifter her a sigh almost level with the flagstones: gleaming in the rain, and with full steam-up for departure, she floated in a mewing circus of gulls.”

When he’s taken in when lost in the cold in by a family of rural German farmers:

“There was something else here that was enigmatically familiar. Raw knuckles of enormous hands, half clenched still from the grasp of ploughs and spades and bill-hooks, lay loose among the cut onions and the chipped pitchers and a brown loaf broken open. Smoke had blackened the earthenware tureen and the light caught its pewter ladle and stressed the furrowed faces, and the bricky cheeks of young and hemp-haired giants… A small crone in a pleated coif sat at the end of the table, her eyes bright and timid in their hollows of bone and all these puzzled features were flung into relief by a single wick from below. Supper at Emmaus or Bethany? Painted by whom?”

You can’t write anything apathetically; you’ve got to climb back to the surface of life where the moments and individuals count, individually

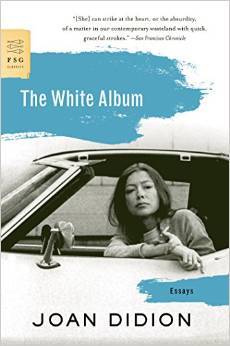

The 2014 Book List, Part III

The stirring conclusion to my 2014 reading…

In 2014, I read 20 fiction & non-fiction books. Here are numbers 1-8 ranked in order of my own most subjective preference. Not necessarily in order of literary greatness, but in terms of my enjoyment of the book, whether it dazzled me with language, or made me think new thoughts, or made me want to make things, or stayed with me long after I read it, or made me feel something, or all of the above.

A couple of asides:

– I’m a little chagrined that my 2014 Didion obsession coincided with this Didion-cultural-moment thing that culminated recently (the Céline ad, the consequent think pieces in The Awl, The Atlantic, another strange one in The LA Review of Books). (Oh jesus, I just spotted another one in The Cut I haven’t read.) It felt personal and intense (as writerly obsessions tend to feel), for reasons that had to with the writing itself rather than whatever Didion the person happens to signify (contrary to what The Awl essay seems to suggest). (I avoided, for example, A Book of Common Prayer, as I, as a Latin American, wanted to avoid a white-lady-abroad account of a made up Latin American country.)

– I’m wondering if the dominance of the big novel is finally fading? Not just with me, but generally, out there? Perhaps our time requires a different genre? Didion is one of many writers that I have found most compelling, exciting, masterful, needed now, whose best work is not the big novel. Others include: Grace Paley, Alice Munro, (short stories); Sontag (essays); Renata Adler (experimental novels, I guess); Anais Nin, Violette Leduc, Sheila Heti, Mathias Viegener, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Eileen Myles (hybrid journal, autobiography, memoir type stuff)…

Anyway, the list:

1. Madness, Rack and Honey (Wave Books, 2013) – Mary Ruefle

A compendium of her wise and brilliant lectures, primarily for readers and writers of poetry. Ruefle is so funny if you’re paying attention, like someone with a quiet voice who is acerbic and witty, but overshadowed by the loudmouths in the room. I especially loved the essays, “My Emily Dickinson,” “On Beginnings,” “Poetry and the Moon,” and the title essay.

2. The White Album (1979) – Joan Didion

Slouching Towards Bethlehem is maybe overall a stronger collection, but “The White Album” is an essay I couldn’t recover from. I read it at least three times. The form resembles the message. Disparate pieces, fragments, including her own anxiety and paranoia, create the unsettling picture of 1968-1969.

3. My Struggle (Vol 1) (2012 in US, 2009 in Norway) – Karl Ove Knausgaard

There has been a lot of focus on how the tediousness of the everyday functions in Knausgaard’s project, but I think the books would be better off without that element. For example, this volume became truly powerful and moving in the last third, when he has to deal with the death of his father (not a spoiler), both the physical and spiritual details of it. That is, when something actually happens. The details, however exhaustive, serve a function. The father has been a long shadow from the first image in the book, a truly artful structure. I felt it viscerally and closed the book permeated with the experience.

But it could do without the 70-page account of buying beer and having a lame New Year’s Eve when he was 15… I also love his philosophical meanderings, thoughts on modern life, which are also not part of the tediousness. I’d like to see them as stand-alone essays (for example, the digression about the mystery of visual art, why a particular painting might move you, or another about 17th-century vs. 21st-century consciousness).

4. My Life in France (2006) – Julia Child & Alex Prud’homme

This book is an argument for making the bold move. Julia Child didn’t start cooking seriously until she and her husband moved to Paris when she was in her late 30s (still “very young” as she charmingly puts it). They had had adventures in China and Sri Lanka, both working for the State department. They later lived in Marseilles, Germany, Norway, and found elements to love in all of those places .Her voice in this book is enthusiastic, but also no-nonsense, crisply descriptive. It makes you want to love life, live your life, love your partner.

5. The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) – Joan Didion

I was afraid of this book, as if coming closer to the stroke of tragedy running through it would open the door to tragedy; funny, this is the sort of “magical thinking” she’s examining. I liked this best as a portrait of a solid marriage. Happiness is described through detail, without commentary.

6. Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) – Joan Didion

My favorite pieces were the “personals” – “On Keeping a Notebook,” “On Self-Respect,” “On Going Home.” “Goodbye to All That” is unforgettable. I found the title essay sort of pearl-clutching. I realize her point was to bring a different, sobering take on the Haight-Ashbury scene, but the lens was too small, or too filtered through her own darkness, perhaps?

7. The Group (1963) – Mary McCarthy

This struck me as a brave act in its time, so frank and unapologetic about women’s perspectives on sex, sexuality, social classes, work, power relations with men. It’s also expansive, in contrast with the compression favored by a lot women writers. It becomes an implied declaration that it’s all worth writing about, expansively, that such matters should indeed take up some room. Vivid, carefully drawn characters. A different take on New York in the 1930s – these characters inhabit the rich stratosphere above the Great Depression.

8. Play It As It Lays (1970) – Joan Didion

Not a word out of place, and it could not be more bleak. I love this length for a novel (about 150 pages); Didion has said she prefers novels that can be read in a single sitting.

POETRY that passed through 2014

Poetry always gets the shaft in book lists,* maybe because of the way we read it. Or at least the way I read it: A book calls to me from a shelf, I read some poems from it, and it lives on my bedside table for a couple of weeks. I read a poem from it before bedtime or at the breakfast table for a while, I put the back on the shelf. (At any given time, there are a handful of poetry books on the shelf I haven’t read.) Newer poems and poets I tend read online, or in journals.

Poetry is a different substance, physically, than fiction. I don’t have a sense of having completed a book of poetry in the way I do a novel. Rather, the poems are always burning, existing somewhere, even if I’m not looking at them. It’s harder to track this reading over time, poems come in and out as I need them. I’m easily overwhelmed by poetry if I try to read it systematically, which is why it’s hard for me to keep up with the many excellent books published every year.

That being said, here’s a selection of poetry books that spent time next to my bed. Without much commentary, but ordered by the ones that gave me what I needed most at the time:

Noose and Hook (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010) by Lynn Emanuel

The poetry book I most needed this year. Sometimes poems open up for you and sometimes they remain closed. These were open for me. Here’s a good one.

Waterworn (Fly by Night Press, 1995) by Star Black.

Phenomenal, dazzling sonnets. Here’s one.

Selected Poems (University of California Press, 2000) by Fanny Howe.

The Fanny Howe book I return to most often. Poem sequences full of mystery, like private prayers.

The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems by Tomas Transtromer (trans. Robin Fulton) (New Directions, 2006).

A stillness, a relief of silence surrounds much of his work.

Ariel: the Restored Edition by Sylvia Plath (Harper Perennial, 2005 edition, original 1963).

This is the version her daughter put together, restoring Plath’s original order. I read it back to front (a frenzy of bees!) this time around.

Short Talks (Brick Books, 1992) by Anne Carson.

I was excited to find this little book, which was published before she got big, and is excerpted in the more widely available collection Plainwater. I picked this up at a poetry-only bookstore in Boulder, CO called Innisfree.

Black Series by Laurie Sheck (Knopf, 2001)

Words that remained: Ash, unfastening, gauzy.

Tres by Roberto Bolaño (New Directions, trans. by Laura Healy 2011, original 1993)

Bilingual edition. Prose poem sequences.

Meat Heart (Publishing Genius Press, 2012) by Melissa Broder

Caustic, searching, dirty.

My Dead (Octopus, 2013) by Amy Lawless

The inside speaking.

Take It (Wave Books, 2009) by Joshua Beckman

Funny, wandering, untitled.

Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexual (Penguin Books, 2014) by Patricia Lockwood.

Probably the poetry book that made the biggest splash last year. I picked it up after reading that long New York Times Magazine feature.

Some Trees (1956) by John Ashbery

His first book, winner of the Yale Younger Poets Prize.

Poetry journals online that I read: Coconut, BOMB Magazine’s First Proof, Sink Review, and Sixth Finch. I also sought out poems by Mary Ruefle online after reading her book of essays.

* This was originally posted as an addendum to my book list, but I realized poetry should be given its due.

The 2014 Book List, Part II

In 2014, I read 20 fiction & non-fiction books. Here are numbers 9-15 ranked in order of my own most subjective preference. Not necessarily in order of literary greatness, but in terms of my enjoyment of the book, whether it dazzled me with language, or made me think new thoughts, or made me want to make things, or stayed with me long after I read it, or made me feel something, or all of the above.

9. The Flamethrowers (2013) – Rachel Kushner

The first half of this novel is a great ride: sexy, compelling and exquisitely, carefully written. Big and bold, and most fantastically from the point of view of a young female artist navigating the 70s art world in New York, a strong outsider. It is dazzling and blinds you to some of the structural problems with the novel, or maybe the experience allows you to forgive some of the contrived turns and slow-fizzle ending.

10. My Struggle (Book 2) (2013 in US) – Karl Ove Knausgaard, trans. Don Bartlett

I was resistant to the whole idea of this project. (From the New York Times review : “Why would you read a six-volume, 3,600-page Norwegian novel about a man writing a six-volume, 3,600-page Norwegian novel? The short answer is that it is breathtakingly good, and so you cannot stop yourself, and would not want to.”) I generally admire and seek out brevity in novels and plays written in the 20th century and after. So much can be done in 200 pages (see Marguerite Duras’ The Lover, for example.) A big demand on the reader/viewer’s time must be justified. I also felt strongly that a woman with a similar project would never receive the sort of attention Knausgaard has gotten. (Katie Roiphe wrote a piece about this in Slate. (I’m surprised to be linking to a piece by her.)) But I realized these were not good reasons not to read it. My curiosity was piqued every time I flipped through it at the bookstore, and I was interested in its experimental approach to plot and genre – so much of what I’ve enjoyed in recent years doesn’t fit in a clear category (The Diary of Anais Nin, How Should a Person Be by Sheila Heti, Speedboat by Renata Adler, Violette Leduc’s memoirs, etc.)

I didn’t find the second volume (which is embarrassingly subtitled “A Man in Love” for U.S. audiences) as powerful as the first (ranked higher up on my list), and it didn’t make me want to read any more of the series. It explores his sudden move to Sweden and start of new life. Falling in love, having children, feeling trapped, as a writer, and feeling love and a new sort of fulfillment at the same time. The daily frustrations and tedium of child-rearing, the inherent conflicts with a dedicated intellectual life. In a way, this was like reading something from the future because it’s set in Sweden and house-husbands are commonplace, which was entertaining. One of my favorite scenes is his enraged and humiliated attendance at a baby rhythm class taught by a hot young instructor.

He breaks the essential rules meted out to beginning writers: don’t include scenes that don’t propel the action; ensure that every word is necessary. I read many reviews seeking to justify the tediousness – the boredom is part of the point, or the excruciating detail is what makes you feel like you’re living there with him. I sort of understand this, but I can’t say it wouldn’t be good if you cut that daily-life stuff out. I enjoyed it best when he dug deep, the philosophical digressions on the contemporary consciousness vs. the Baroque sensibility, on what it means to write, on the mysterious way you are either open or closed to a poem, etc.

11. The Berlin Stories (1945) – Christopher Isherwood

A collection of two novellas, The Last of Mr. Norris (a single narrative) and Goodbye to Berlin (a series of sketches, all with the same narrator, which inspired the musical Cabaret). I almost wish I had encountered the two works separately because I wanted the second half to be like The Last of Mr. Norris and was a bit disappointed when it wasn’t. Mr. Norris was so funny – witty, absurd and dry in only the way the British can be. Great characters in both halves, extremely vivid, like the stiff aristocrat who wears a monocle, is into body-building and enjoys English adventure stories of shipwrecked boys in a pervy way. Goodbye to Berlin has a bigger emotional range and made me think of the continuity of certain aspects of city life across the ages (dive bars, class divisions).

12. Ghost World (1997) – Daniel Clowes

Brings back in full force the extreme smart-ass, sometimes super-funny, sometimes really mean spirit of the late stages of high school. I got the feeling this started as a weekly and the plan for a graphic novel came later, as not much happens for a while in the beginning, although it’s fun (the girls hanging out, going to the weird diner), and all of the action comes quickly and heavily at the end. Visually very funny, too.

13. The Jaguar Smile (1987) – Salman Rushdie

Rushdie’s non-fiction account of being a visiting writer in the hopeful, Sandinista-led Nicaragua, recovering from civil war (pre-Satanic Verses and next-level fame). He’s a charming and sympathetic narrator and gives a vivid account of politicians, poets, midwives, children, in various regions of the country. I read this while visiting Nicaragua and it was a good way to learn a bit of history; it was also interesting to see all of the changes that have taken place since Rushdie was there. I liked that his frame of reference is another part of the “developing world” (India/Pakistan), and many aspects of Latin American life are familiar, while issues like hunger and poverty are more acute in some ways where he’s coming from, a refreshing departure from the usual Western-person-abroad travel literature.

14. The Voyeurs (2012) – Gabrielle Bell

Second time I read this collection of confessional, very Brooklyn comics, including an account of her relationship with Michel Gondry. I enjoyed this more the second time around as I knew what to expect and lingered in the artistry a bit more. (The first time I was surprised by how emotionally raw some of them are, examining depression and anxiety in a way that brings you close.) I often think of one particular comic about the meaning of compulsive e-mail checking, what it is you’re wanting from a new message.

15. Run River (1963) – Joan Didion

This was my year of Didion, I couldn’t get enough. This is her first novel, before her lean and rhythmic style had fully developed, which was interesting to see. What remains most clearly with me is her protagonist, Lily, so clearly drawn – passive, distracted, frail, but at the same time calculating somehow, driven by sex. In a Paris Review “Art of Fiction” interview, Didion said someone had described her novels as romances; this pleased her and she agreed to some degree, which is funny, but I think there’s also something there. The plot is a secondary concern and problematic in some ways, especially the ending, but it is a first novel, after all.

The 2014 Book List, Part I

In 2014, I read 20 fiction & non-fiction books. Here’s the tail-end of the list, ranked in order of my own most subjective preference. Not necessarily in order of literary greatness, but in terms of my enjoyment of the book, whether it dazzled me with language, or made me think new thoughts, or made me want to make things, or stayed with me long after I read it, or made me feel something, or all of the above. (This also includes an addendum on poetry and the books I abandoned.)

16. Like Life (1990) – Lorrie Moore (Vintage)

Lorrie Moore is usually categorized as a funny writer, and she is. But she is consistently devastating, too. Nobody talks about that. I had read this book in 2007 and it depressed the hell out of me then. This time I couldn’t get through some of the stories, she takes the pain so far. “The Jewish Hunter” is my favorite, maybe because some genuine human connection actually takes place (although it’s not lasting).

17. Laughable Loves (1969, 1974 in English) – Milan Kundera (Harper Perennial)

It’s not worth getting offended over Kundera’s attitudes towards women as his books are almost quaint time capsules of a certain attitude, at this point. In that spirit, I enjoyed these stories, pretending I was a roué Czech doctor for a little while. He’s also deft in depicting the ways a corrupt Communist state infiltrates all parts of life.

18. In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto (2008) – Michael Pollan (Penguin Books. Bought at Human Relations bookstore in Bushwick)

I think this could have worked as a long essay, especially if you’ve read the revelatory Omnivore’s Dilemma. I read this early in the year and can’t remember too much about it, actually, but maybe this is because so much of Pollan’s thinking has permeated our language around food choices and politics (“Eat food, mostly plants,” etc.).

19. Animal, Vegetable, Miracle (2007) – Barbara Kingsolver (Harper Perennial. Received as a gift, sold it to a used bookstore)

A non-fiction account of how Kingsolver and her family moved to a farm in Virginia to live the true locavore lifestyle, growing or raising all of their own food, or procuring it from a 100-mile (I think?) radius. It gave me a new appreciation for the knowledge and work small-farm farmers do. The book is at its best when she gets deep into the details of farm life, for example, about the mating lives of turkeys. I was less interested when she wrote as an advocate and called on the reader to take similar actions (for example, get a second freezer in order to eat local throughout the winter), particularly as I am already fairly educated about the environmental and political issues surrounding food production and distribution, and am doing the best I can. At those times it came off as preachy or defensive. Also, I just can’t take on feeling guilty for eating bananas at this point at my life.

20. The Sense of an Ending (2011) – Julian Barnes (Vintage)

I love Julian Barnes (especially Flaubert’s Parrot), but I didn’t like the narrator in this story, who kept insisting on his ordinariness, a conceit that seems played out. I think it was a device here, Barnes emphasized the protagonist’s cluelessness in order to keep twisting the plot, in a clever way. Ultimately, it felt to me like the book was about its own cleverness and didn’t convince me on an emotional level.

BOOKS ABANDONED

I Love Dick – Chris Kraus (1997)

I was really ready to love this book, I was excited when I bought it. I liked everything about it in theory – the loose form, the fact that it deals with issues of sexuality, gender, open relationships, feminism from a personal perspective – but I don’t know what happened. It didn’t hold my interest. Maybe because Kraus is so obsessively internal, letters about letters. I got claustrophobic. I even tried twice with it.

Z a novel of Zelda Fitzgerald (2014) by Therese Anne Fowler

I couldn’t get past page 3. Not at all how I would imagine Zelda Fitzgerald’s voice. This is like the Hollywood version, or the version made for a docile book club.

Et après… par Guillaume Musso

Picked this up in an attempt to keep up my French. And actually, it made me feel good about my French because I could tell it was badly written! (Schlocky, clichéd.) Also, it takes place in New York! If I’m going to read a book in French I don’t want to be back in NYC

from “The Subway Platform”

And the people all around me, how many hadn’t

at some time or another curled up in their beds with the shades drawn

not knowing hot to feel the forwardness, or any trace

of joy? Wing of sorrow, wing of grief,

I could feel it brushing my cheek, gray bird

I lived with, always it was so quiet on its tether.

Laurie Sheck, from her poem in the book Black Series (2001)

Convinced by Best of 2014 Lists…

I can’t stop reading “best of” lists. Book lists are irresistible, “best of” lists even more so. Here are a handful of recurring books on these lists that have definitively made it on my “to read” list. (I looked at best of lists from the NY Times, the LA Review of Books, McNally Jackson Bookstore, the LA Times, Words Without Borders, a couple of Flavorwire lists…probably others). I’m including the presses, because it is becoming increasingly apparent to me how the identity of a press matters and how important small presses are:

The Neapolitan novels (Europa Editions), the trilogy by Elena Ferrante, translated from Italian. These first came to my attention at my favorite Brooklyn bookstore, Spoonbill and Sugartown. Books that generate obsession obsession with these books. I also like how Ferrante has avoided all media and public appearances, such a rebellious stance in these times.

The Wallcreeper by Nell Zink (Dorothy, A Publishing Project). Sounds imaginative, wild, funny. Also, way to hit it out of the park, small press!

A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing by Eimar McBride (Coffee House Press). Novel, Irish author. Written in its own sort of language. I was intrigued on hearing the title alone.

Citizen by Claudia Rankine (Graywolf Press). So many poets I know have been declaring that this is the book America needs right now, in the time of protests over racial injustice, the long-bubbling unspoken problems, tensions, violence.

The Unspeakable a by Meghan Daum (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux). Essay collection. I’ve read a couple of interviews with Daum where she says such smart and unusual things so succinctly. I also loved her essay about not having children, which is in here (first appeared in the New Yorker).

And on my “might read” list:

The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison (Graywolf Press). Essay collection, so much acclaim. An interesting subject.

On Immunity by Eula Biss (Graywolf Press). Non-fiction. I’m not that interested in the subject (the anti-vaccine movement), but I think she makes it about much more than this. I was also blown away by her writing in an essay I read in The Believe.

Stoner by John Williams (New York Review Books Classics). Reissues. I read an essay in praise of it and have seen it around. Slim and quiet, how I often like novels…