When I look around today, the biggest anachronism I see is pregnancy. I just can’t believe that people are still pregnant.

I can never get over when you’re on the beach how beautiful the sand looks and the water washes it away and straightens it up and the trees and the grass all look great. I think having land and not ruining it is the most beautiful art that anybody could ever want to own.

I suppose I have a really loose interpretation of ‘work,’ because I think that just being alive is so much work at something you don’t always want to do. Being born is like being kidnapped. And then sold into slavery. People are working every minute. The machinery is always going. Even when you sleep.

Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol

Before I was shot, I always thought that I was more half-there than all-there – I always suspected that I was watching TV instead of living life. People sometimes say that the way things happen in the movies is unreal, but actually it’s the way things that happen to you in life that’s unreal. The movies make emotions look so strong and real, whereas when thing really do happen to you, it’s like watching television – you don’t feel anything.

Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol

He concludes that he was indeed watching television, including when he was being shot and ever since…

The red lobster’s beauty only comes out when it’s dropped into the boiling water … and nature changes things and carbon is turned into diamonds and dirt is gold … and wearing a ring in your nose is gorgeous.

Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol

For a while we were casting a lot of drag queens in our movies because the real girls we knew couldn’t seem to get excited about anything, and the drag queens could get excited about anything. But lately the girls seem to be getting their energy back, so we’ve been using real ones a lot again.

The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975)

For all his masks, truth-as-quips, posturing, disingenuousness, I feel some of Andy Warhol the person comes through in this book. It’s also really funny. He outs himself as a serious sugar fiend (being rich means having money to buy candy), often refers to his burning desire to have his own TV show called “Nothing Special” (why didn’t they give that man a TV show?!). He confesses a preference for “Talkers” over “Beauties” (Talkers do, Beauties are), for bad performances over good performances (it’s impossible for bad performances to be phony), an obsession with perfumes, trapping memories through scent.. I do think his love of all things American is genuine. (Wikipedia informs: “The Philosophy was ghostwritten by Warhol’s secretary Pat Hackett and Interview magazine editor Bob Colacello. Much of the material is drawn from conversations Warhol had taped between himself and Colacello and Brigid Berlin.”)

For all his masks, truth-as-quips, posturing, disingenuousness, I feel some of Andy Warhol the person comes through in this book. It’s also really funny. He outs himself as a serious sugar fiend (being rich means having money to buy candy), often refers to his burning desire to have his own TV show called “Nothing Special” (why didn’t they give that man a TV show?!). He confesses a preference for “Talkers” over “Beauties” (Talkers do, Beauties are), for bad performances over good performances (it’s impossible for bad performances to be phony), an obsession with perfumes, trapping memories through scent.. I do think his love of all things American is genuine. (Wikipedia informs: “The Philosophy was ghostwritten by Warhol’s secretary Pat Hackett and Interview magazine editor Bob Colacello. Much of the material is drawn from conversations Warhol had taped between himself and Colacello and Brigid Berlin.”)

My favorite parts: a chapter on art, describing an heiress trying to live out her “art fantasy” with him by describing him as having taken serious risks with his art. He replies that anyone who cuts salami (for example) is taking a risk (of cutting themselves) and that she’s insulting stuntmen, babysitters, the men who landed on D-Day (etc.), because they really know what it means to take a risk, not artists. The last chapter, which describes him dragging one of his snobby young Factory employees with him to buy underwear at Macy’s is wonderful, too.

Sometimes he speaks in the poetic, and by that I mean he describes an idea centered on an image rather than on a rational, explanatory system. For example, on space:

“My ideal city would be one long Main Street with no cross streets or side streets to jam up traffic. Just one long one-way street. With one tall vertical building where everybody lived with:

One elevator

One doorman

One mailbox

One washing machine

One garbage can

One tree out front

One movie theater next door

"Main street would be very, very wide, and all you’d have to say to someone to make them feel good is, ‘I saw you on Main Street today.’

"And you’d fill you car up with gas and drive across the street.”

Etc. This isn’t meant literally. People wanted to take him literally which is why he made them angry.

There is a cold-blooded edge to parts of it, the posture is that sex and emotions are a waste of energy, which is also him being self-deprecating in a way, funny. He describes himself as having hurried along his development (dying his hair gray at age 24) so that he could have old problems instead of young problems (which involve more sex and emotions). He puts it in terms of movies vs. television. Movies are intense real emotions; TV is always on, you are always doing something else when watching TV, it’s a drone. He prefers TV. He refers to his tape-recorder as his wife. He’s prescient about describing emotions in terms of chemicals. He never addresses his sexuality.

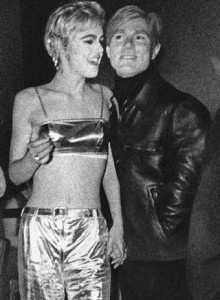

He has a chapter on Love, which is subtitled “The Fall and Rise of My Favorite Sixties Girl”. It’s a thinly veiled portrait of Edie Sedgwick (he refers to her as “Taxi”), and it’s really mean. He essentially paints himself as always having been simply been fascinated with her in a traffic accident sort of way & describes her as manipulative, selfish and dirty (literally). He puts down any sort of fashion acumen she may have had by attributing her style simply to her being cheap (hence the miniskirts) & attempting to shock her parents. His whole attitude is detached. But by preceding the chapter with the following, in a way, he’s owning his own lack of compassion:

“During the 60s, I think, people forgot what emotions were supposed to be. And I don’t think they’ve ever remembered. I think that once you see emotions from a certain angle you can never think of them as real again. That’s what more or less happened to me.

“During the 60s, I think, people forgot what emotions were supposed to be. And I don’t think they’ve ever remembered. I think that once you see emotions from a certain angle you can never think of them as real again. That’s what more or less happened to me.

"I don’t really know if I was ever capable of love, but after the 60s I never thought in terms of ‘love’ again

"However, I became what you might call fascinated by certain people. One person in the 60s fascinated me more than anybody I had ever known. And the fascination I experienced was probably very close to a certain kind of love.”

(Edie & Andy image I got here.)

Thoughts on Raymond Carver’s Cathedral

While reading fiction, I mark passages that strike me in a writerly way, but this didn’t happen while I was reading the collection Cathedral. I do think Carver’s a brilliant writer, but his genius is in pacing, dialogue. I admire his use of profanity. He has a way of inserting “Goddamn” that’s so funny.

While reading fiction, I mark passages that strike me in a writerly way, but this didn’t happen while I was reading the collection Cathedral. I do think Carver’s a brilliant writer, but his genius is in pacing, dialogue. I admire his use of profanity. He has a way of inserting “Goddamn” that’s so funny.

People talk about Carver in terms of realism, telling working people’s stories in a realistic way, but I always thought his world is stranger, more dislocated than that. Take the story “Feathers” about a couple going to another couple’s house for dinner – there are the grotesque teeth sitting on the TV, there’s a peacock named Joey, there’s a hideously ugly baby. Oh, there’s a good line: “Even calling it ugly does it credit.” Or “Fever”, a story of a man whose wife has left him, left him alone with their two young kids. He makes her sound a little crazy when she calls on the phone, yes, but she is also genuinely psychic in a way. The bereft husband never questions how she knows what she knows – this is a conscious move on Carver’s part, it makes it eerie, almost, or more about the man’s psyche than what’s happening in reality.

Stories about marriages ending. A recurrent theme of children spoiling relationships (“Feathers”, “The Compartment”). The grip of alcoholism: in “Vitamins” it’s still kind of a lark, turning dark; “Where I’m Calling From” & “Chef’s House”, fully in the dark side. The couple seems to be the central figure, the couple relationship is at the heart of all of the stories, in a way.

Hard to pick a favourite, I guess “Cathedral” is the obvious choice, it may be Carver’s single best story – so funny, effortless, effervescent. The way he establishes the relationship between the couple – the husband (narrator) is doing his best, “on notice”. He loves his wife, he often disappoints her. She really wants her blind friend to like him, is hoping her husband doesn’t do anything embarrassing. The narrator places you on his side from the beginning, & it feels comfortable there (“A beard on a blind man! Too much I say.”) The use of exclamation marks. It suddenly goes to a metaphysical place, but from this wise guy’s perspective. How do you describe a cathedral to a blind man? It leads to a connection he didn’t think himself capable of.

Full ranking in order of preference:

“Cathedral”

“Feathers”

“Vitamins” (Hard to forget this story.)

“Where I’m Calling From”

“Fever”

“The Bridle” (How life kicks people when you’re down sometimes. The only story with a female narrator, interesting how she feels bound to the woman she’s describing.)

“The Compartment”

“Chef’s House”

“A Small, Good Thing”

“Preservation”

“Careful”

“The Train” (more like a sketch, a beginning of a story than a story proper)

The real artist is never concerned with the fact that the story has been told, but in the experience of reliving it; and he cannot do this if he is not convinced of the opportunity for individual expression it permits.

Anais Nin, The Diary, Volume 1.

[She writes this in the context of her analysis with Otto Rank. How he, unlike other analysts, doesn’t seek to fit the individual’s story into a pattern in a textbook, a case of X or Y neurosis, but rather delights in each individual’s story, including the ways in which it mirrors an archetype or “textbook case”, in its own unique way. Her example – that he approaches like “an artist when he is about to paint, for the thousandth time, the portrait of the Virgin and Child”.]

Page 295

…an exercise in creation

My father left: love means abandonment and tragedy, either be abandoned or abandon first, etc. Not only the leap over the obstacle of fatality, but a complete artistic rehearsal of the creative instinct which is a leap beyond the human through a complete rebirth, or perhaps being born truly for the first time. To accomplish this it was not sufficient that I should relive the childhood which accustomed me to pain. I must find a realm as strong as the realm of my bondage to sorrow, by the discovery of my positive, active individuality. Such as my power to write […] the most vital core of my true maturity.

Anais Nin, The Diary, Volume 1